Discours, figure 50 Years After

Lyotard, Adorno, and the Critical Line

Sven-Olov Wallenstein

Fifty years ago, Jean-François Lyotard’s thesis Discours, figure was published. Signaling his return to the university after a long period of political activism, the book is the first in a winding series of reflections, interventions, and experiments that all bear on what it means to write about art from a philosophical point of view—but also, and equally important, on why artworks should not simply be placed as objects to be interpreted, but must be given a capacity to respond to, infiltrate, and shift the valences of the philosophical text.

In this he draws close to another thinker, whose final work, dealing with similar questions, had been published in a first version the year before: Theodor W. Adorno’s Ästhetische Theorie. According to Lyotard himself, however, he had not yet read Adorno when he wrote his thesis. Two years later he would suggest, in the preface to Dérive à partir de Marx et Freud (a collection of essays written before 1970), that even though “aesthetics = the studio in which to forge the most discriminating concepts,” this equation, “the one of Adorno (which I had not read at the time), is still not sufficiently drifting”—insufficiently dérivante, in the sense that it remains tied to a negative dialectic incapable of responding to the works of the present (the examples mentioned are Cage, Cunningham, Pop, and hyperrealist painting), which are wholly “affirmative” and indicate the “new position in desire.”[1] While Lyotard marshals many sources, predominantly Marx and Freud, both read against the grain, staking out this distance from Adorno’s project can be taken as one of the crucial tasks, implicit or explicit, that these early essays set themselves. This distance spans across something like a critical line, or more precisely the line of critique: in what sense can artworks be critical without being caught up in a game of negativity that places them—so in Lyotard’s view of Adorno, in any case—as mute objects that can only speak by way of a ventriloquy on the part of a theory already constituted elsewhere?

This drifting-off is performed in Discours, figure and in many of the essays from the late sixties and early seventies, and was eventually placed under the general rubric “libidinal economy,” which is also the title of Lyotard’s book from 1974, after which he began to doubt the validity of the early work, or rather, doubt its underlying thrust to simply expel the very idea of validity, systematicity, and theoretical coherence. This would usher in his turn toward the problem of the postmodern, first in the series of conversations with Jean-Loup Thibaud, Au juste (1977), and then, more famously, in La Condition postmoderne (1979) and the many books that would follow. In view of the preceding, this was something like a sobering up (which is how Lyotard himself sometimes would present it) and a return to traditional problems—ethics, justice, truth—by way of new readings of, above all, Kant, and Wittgenstein.

My aim here is however not to trace a chronological line through Lyotard’s work and to map its many shifts and inflections (for he indeed appears to have changed his mind more often than most other philosophers), but to return to some of the ambiguities, perplexities, and antinomies that traverse the early writings. If there is a chronological line here, I would suggest that it be drawn in a different sense, between Adorno and Lyotard as two conflicting version of the philosophy of modern art: while Ästhetische Theorie concludes and summarizes decades of reflections on modernist art, Discours figure proposes a new beginning at the point where the predecessor left off. I say “modern” tout court because the opposition between terms like “modern” and “postmodern,” while tempting and often used by commentators, have little relevance here. In this period the alternative is available to none of them; for Adorno it would probably have been aligned with the pair progress-reaction, which organizes the reading of Schönberg and Stravinsky in Philosophie der neuen Musik; for Lyotard there is no question of a break with the past, rather the task is to reactivate the radical potential of the avantgarde, especially in the visual arts, for philosophical discourse. In this sense, both are emphatic modernists, and what separates them is the conclusion to be drawn from this, but also, and equally important, the status of theory as critique, of the medium of concepts that bear on negativity, not some divide between a Before and an After.

In fact, as Lyotard would say a decade and a half later when he began to look again to Adorno, this time for a positive support, beginning with Discours, figure onward his works can be read as drafts for a systematic aesthetic theory that would respond to Ästhetische Theorie, although in a sense that, while drawing on the predecessor, still questions all three terms, the system, aesthetics, and the idea of a theory. That this project remained unfinished should then not be seen simply as failure, but rather as a symptom of the complexity of the subject matter itself, which poses a formidable resistance to the kind of historicizing sweep that on one level was Adorno’s great achievement, but also tended to enclose his theory in a backward-looking and melancholy mood. To emancipate aesthetic theory from predefined notions of subjectivity and experience, and to open it up for the event of the work as something unforeseeable and disruptive, is a task that in some respects can be found already in Adorno, but it also goes against certain parts of his thinking where he tends toward systematic closure, which is why the shadow of Ästhetische Theorie, whether explicitly named or not, looms large over Lyotard’s writings.

From the figure to the figural to the matrix

The claims made in Discours, figure were in many respects foreshadowed already in Lyotard’s first book, La phénoménologie from 1954.[2] Here phenomenology is presented as an attempt to reach down into a pre-predicative layer of experience that, however, is always already lost: “Insofar as this originary lifeworld is pre-predicative, all predication and discourse certainly implies it, but equally lacks it, and cannot properly say anything about it” (Ph 43/68). Husserl’s phenomenology, unlike its Hegelian counterpart, is a radical acceptance of finitude, and if it constitutes a “battle of language against itself aimed at attaining the originary,” it must at the same time account for the fact that “[i]n this battle the defeat of philosophy, of logos, is certain, since the originary, once described, is as described no longer originary” (43/68). This fundamental incompletion will later be emphasized as that which gives phenomenology its very power as a line of resistance against the appropriating power of the absolute idealism of the concept as well as of the linguistic imperialism of structuralism. The insistence of the pre-predicative remains irreducible to every verbal translation; it provokes the linguistic act while hollowing it out from within, and in this way, Husserl shows us how language and the field of sensory experience are always intertwined in the process of signifying without ever achieving a synthetic whole.

These claims were developed in Discours, figure in terms of what is called the figure, the figural and the matrix, where the productive tension with respect to phenomenology as well as to the Freudian theory, which eventually supersedes it, organizes the argument, so that phenomenology and psychoanalysis are played off against each other, and both are, as it were, transgressed from within.

First, the pre-linguistic sphere begins to acquire a more developed depth and presence of its own, instead of being just an obscure and evanescent obverse side of reflexive discourse. “This book,” Lyotard states, “protests: the given is not a text, it possesses in itself an inherent thickness, or rather a difference, which is not to be read, but rather seen; and this difference, and the immobile mobility that reveals it, are what continually falls into oblivion in the process of signifying.”[3] This is what gives visual art its paradigmatic place: “One does not read or understand a painting. Sitting at a table one identifies and recognizes linguistic unities, standing in representation one seeks out plastic events. Libidinal events.” (DF 10/4)

For Lyotard, any conception of autonomous discourse must fail, not because of a nominalism that opposes the singularity and inexhaustibility of the thing to the subsuming power of concepts, but because discourse always relies on being intertwined with a different dimension, that of the visual and perceptual, which he first terms figure. While Adorno is yet not present, we can see the extent to which Lyotard is at once close to and distant from the idea of negative dialectics, which also emphasizes the resistance of particulars to subsumption. For Adorno, too, this does not entail a nominalism implying that we could or should simply step outside of conceptual mediation, only that we must acknowledge that which always unsettles it from within, as Adorno suggests in a preparatory note on the way toward Negative Dialektik: “Not jump over nominalism. Transcend it starting from itself.”[4] Similarly, Lyotard does not suggest that we would get a more direct purchase on the world by moving into the space of a pure figurality; for both the particular exerts a resistance to discourse, arising from a difference not just between the sensible and the intelligible, but inside the sensible as such, while the questions where they seem to diverge is whether the idea of mediation at all can do justice to this.

Rather than a dualism opposing concept and particular, language and the visible, Lyotard suggests that the figural and the discursive must be understood as always already related. The figure is both outside and inside discourse; it is what demands an opening toward the world for language to function at all, and the world of reference bracketed by Saussure (even though this for him was a purely methodological move, not a metaphysical one) must be retained: language is in its essence traversed by referential and indexical elements that point to its outside. Inversely, the visible domain is as such never a plenitude resting in itself, but is always shot through with gaps and lacunae, and it is only given through a diacritical force of distancing and spacing that calls upon the signifying power of language. But beyond this, what prevents these two orders from resting within themselves is what Lyotard calls difference itself, a divide that does not pass simply between the sensible and the intelligible, or between perception and language, but is the inner fault line that traverses both and makes them into what they are. The choice of terms obviously generates a set of further problems, above all what the “itself” of difference might mean. In this, Lyotard’s “difference” fares no better than all other such quasi-transcendentals, for instance, in the French context, its more famous counterpart in Derrida, différance, which always, just as analogous terms such as trace, spacing, writing etc., run the risk of becoming the kind of arche or principle that it attempts to displace. But instead of chastising this as an inconsistency, we should see it as an instance of the “battle of language against itself aimed at attaining the originary” that Lyotard located already in Husserl, a struggle in which any victory would be equivalent to a failure that remains blind to its own finitude.

This interlacing notwithstanding, there is still a strategic priority that is accorded to perception: the book, he says, is written “in defense of the eye,” and it insists on the autonomy of the sensible vis-à-vis the discursive in a way that pursues a phenomenological task. But in the end, Lyotard still perceives phenomenology as too dependent on a philosophy of the subject that forecloses the “event”-like dimension of the work, and his alliance with the phenomenology of perception is in this sense only partial and strategic. The eventfulness of the “gesture” in Merleau-Ponty still remains tied to a subject of constitution, Lyotard claims, and the passivity of perceptual synthesis that should account for the donation of the visible cannot avoid being caught up in an opposition to intentional activity, which means that we ineluctably tend to understand it as an underlying support.

If phenomenology moves in the direction of a field of pre-conceptual sense in which events may take place, it is for Lyotard still unable to account for their very irruption, since it tends to absorb and integrate them into the already habitual. The event must come from elsewhere than from the already formed body, or from the world as a depository of sense—concepts that in fact ensure that the phenomenology of perception remains a happy philosophy. Truth, Lyotard will say with reference to Freud, is what detonates, it overflows constitution, or rather tears it apart, instead of supporting and grounding our relation to the world: “one will have to give up phenomenologizing, if one wants to reach this something that comes close to phenomenological constitution, this something that is not constitutible, but only graspable through an entirely different method—deconstruction—and on grounds of completely other, unexpected effects—of recessus” (56/55).

It is because of his ultimate rejection of phenomenology in favor of psychoanalysis as a theory of the lost object that Lyotard will eventually resist the move towards fusing philosophy with poetry; no discourse possesses its object, and philosophy, neither an art nor a science, born “at the same time as the world or the gods cease to dwell in the world” (DF 57f/56, mod.), must learn to speak soberly, at a distance, without fantasizing of a fusion with the world. This notwithstanding, there is an exchange between the two, and philosophy can in this way profit from the arts.

Stéphane Mallarmé, Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (1897), autograph layout from 1896.

That one of the crucial examples offered to Lyotard is Mallarmé and his poem on the dice-throw comes as no surprise. What Mallarmé’s poem shows with unprecedented radicality is in fact a quality essential to all discourse: elements in language are not just oppositional terms (differences relating to other differences), but also stand out as figure against ground, which points to an irreducible opacity in the signifying unit—the graphic form of the letter, where only difference counts, is intertwined with the plastic function of the line, which is seen rather than read; and virtual and textual spaces are constituted by repressing and forgetting the line. The letter and the line are however also mutually dependent; it is always possible to read the letter as line, a visual surplus that also entails a loss of readability, as can be seen in certain forms of medieval art. But if the figural can be understood as a blocking together of these two spheres, the emphasis on the imbrication of letter and line should however not be identified with what at the time was commonly called the “materiality of the signifier,” which usually stayed within the confines of a theory of textuality; for Lyotard, the materiality of the figural has to do with temporality and the event, which for him is a way of countering the idealism of textuality.

Marcel Broodthaers “Exposition Littéraire autour de Mallarmé'” (Wide White Space Gallery, Antwerp, 1969). The exhibition presented a copy of Mallarmé's book with two pages visible, together with a series of metal plates engraved with black impressions representing the text, and a recording of Broodthaers reciting the poem.

In the second part of the book, Freudian analysis and the idea of the unconscious as a radical disruption of the nexus between world and word begin to displace the still too peaceful, pious, and harmonious element of the phenomenological flesh. The true articulation of discourse and figure belongs to the order of an unconscious that radically dislodges all grounding—ultimately also the grounding within psychoanalysis itself to the extent that it aspires to be a systematic theory, Lyotard claims, in a move that surely goes beyond Freud, and takes him closer to some aspects of Lacan’s work from the same period.

This shift means that the figure is brought back into the libidinal, and Freud and psychoanalysis are pitted against both structural linguistics and the phenomenology of perception. We must go beyond these two spaces, that of the system and that of the subject, Lyotard insists, which means to move from the space of sight to that of vision, from the world to the phantasm, and to an object that no longer stands opposed to us in the depth of perceptual space: the elusive object of desire and wish-fulfillment.

This move is prepared in the long transitional section that marks the book’s turning point. Entitled “Veduta on a fragment of the ‘history’ of desire” (163-208/159-201), it is set in italics throughout, as if to underscore its particular status as a long digression inserted before the subtitle “The other space” (“L’autre espace”). In this “view”—where the veduta, as an opening to an “other scene” in a painting, communicates with the opening to the andere Schauplatz of the unconscious invoked by Freud—Lyotard traces the complex interplay of the visual and the textual in the passage from later medieval painting to the Early Renaissance. Crucial in this art-historical interlude is the argument that it is from the advent of the modernist revolution, epitomized by Freud and Cézanne, that we can understand that there is no natural system of representation, no system that would be closer to the truth of perception, and that Renaissance perspective was just as upsetting to those accustomed to what came before it as modernism was at its inception. There is always a dimension of heterogeneity in any representation, visual or textual, and each artistic revolution is both an encounter with this, and a way to conceal it.

Masaccio, Santa Trinità (1425-1427), Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

In all of these examples, from Masaccio’s clashing of incongruous spaces in the Holy Trinity to Cézanne, Lyotard locates various ways of acknowledging another figural space that belongs neither to perception nor to the objects of thought, but only makes itself felt by disrupting both. This also means that the figural begins to be opposed to the figure, which is only one of its manifestations; and aesthetics as a theory of the sensible, of aisthesis, which can still be taken as the topic of the first part of the book, is displaced by energetics. In energetics “the dream-work does not think,” as reads the title to one of the most important sections, where Lyotard’s return to Freud places him in opposition to Lacan: if the dream-work does not think, it is because it does not consist in an ordering and structuring of significations, but precisely performs a work, a violent formation-deformation of the linguistic and visual data that make up its raw material. The picture puzzle, Lyotard suggests, contains all these dimensions that constantly refer us from the text to the image and back again, without any of them forming a stable basis for the others.

From the image-figure, based on recognition and identification, we must proceed to the form-figure, which forms and animates the image from within, and finally to what Lyotard calls the matrix-figure, which is strictly invisible and no longer belongs to the domain of consciousness and perception. This matrix-figure has the structure of a “primary phantasy,” which is neither a pattern nor a schema, neither a shadow on the imaginary screen nor a stage direction to be followed on the imaginary scene. When situated in a textual space it indeed appears as an arche, although, Lyotard suggests, this is a double phantasy, first of an arche, and then of an arche that could be expressed. The phantasmatic matrix in fact means the opposite: the origin is an absence of origin, and everything that presents itself as originary is a hallucinatory figure-image in this non-place.

The matrix is as such neither visible nor readable, neither plastic nor textual, it is what earlier appeared as “difference itself,” and to this extent Lyotard can claim that discourse, image, and form all remain outside of it, since it exists in all three spaces simultaneously. If the matrix resembles anything, we should rather think of Freud’s originary repression: that which is furthest away from our understanding and disappears as soon as it becomes either sensible or intelligible. The matrix forms only by deforming, it founds by withdrawing, and it makes discourse and signifying, Gestaltung and the image, possible by leaving in them an ineradicable trace of the invisible –no longer the “invisible” of Merleau-Ponty, which, even though it is “the invisible of this world,” i.e., always arises from the flesh, still has to do with the transcendence and lightness of the idea, whereas Lyotard’s invisible is buried in the depths below the flesh.

If the “other scene” of which Freud speaks cannot be represented, it is because the matrix remains a radical and ex-centric other in the constitution of consciousness, to such an extent that it cannot even be opposed to consciousness. The locus of desire is utopia, Lyotard repeats on many occasions, which means not only that we must “renounce once and for all finding a place for it” (DF 19/14), for instance within the quasi-transcendental structure of castration as proposed by Lacan, but also that its non-locality allows it to overflow all boundaries, so that in the end theoretical work itself can be taken as a particular mode of desire—a conclusion that Lyotard does not yet draw, however. In Discours, figure the excavation of the workings of desire is still somewhat uneasily presented as a “practical critique of ideology,” or even a “detour on the way to this critique” (19/14), which attempts to combine two strands, a theory of desire that wants to transform praxis in the name of a truth opposed to ideology, although soon the concept of ideology would appear misleading, or at least no longer possible to overcome in a “true” theory. Discours, figure in this sense places itself at the critical line, ceaselessly moving back and forth between seemingly incompatible positions, and generating a tension that would return in constantly new guises.

Enter the devil himself

If Discours, figure was an attempt to rethink phenomenology, or rather push it into the space of the “figural,” Lyotard’s writings from the early seventies can be read as an extended debate with critical theory and a plea for the possibility of a thought that would more emphatically take leave of the negative, in which he subsequently would also include the figure, the figural, and its derivations: the category of the figure, he now suggests, “remains caught in the net of negative and nihilist thought” (DMF 18). And while the earlier response to the phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty was ambivalent, in the sense that it provided Lyotard with a path towards a reevaluation of the sensible from which he finally, however, felt a need to depart, the initial remarks on Adorno display a more straightforward need to expulse the predecessor, and to begin precisely with what is impossible or unacceptable from his position, by crossing the critical line.

In the essay “Adorno come diavolo” (1972) Lyotard comments on the reading of the trajectory of modern music proposed in Adorno’s Philosophie der neuen Musik, where Schönberg and the formal, de-subjectifying construction of twelve-tone music is that which bids halt to dialectics, although dialectically, which is the position that Lyotard wants to overcome. It was Adorno’s entanglement in a certain philosophy of the subject, he suggests, that forced him to understand its fracturing in late capitalism as a simply tragic and negative phenomenon. In this negative dialectical equation, art was called upon to bear the burden of diremption, to testify to the negativity of the dissolved and disempowered subject, and it had to become a kind of demythologized version of religious suffering against which Lyotard pits his own paganism:

Just as Marx, Adorno sees the dissolution of subjectivity in and through capitalism as a defeat: he can only overcome this pessimism by making this defeat into a negative moment in the dialectic of liberation and in the conquest of creativity. […] The category of the subject is not criticized. Not only is it the core of the interpretation of society as alienation and of art as a witness and martyr, but also of the whole theory of expressivity. (DP 99)

If the artist in Adorno’s version had become someone who, with a willfully paradoxical formula, simply realizes his own intentions, which themselves are externalized in a system, thus foreclosing the mimetic impulse that belongs to the full sense of the subject in favor of construction and technical mastery, then, Lyotard suggests, the artist is rather someone who realizes “anonymous intensities” (DP 99) that pass through both subject and system. Our “kapitalism” (the spelling with k, frequent in Lyotard’s essays from the period, signals the link to Marx and Das Kapital) is not so much tragic as it is energetic; the theater of critique is now invested in all its elements and its former distinctions are erased in favor of a continuous surface that folds and twists, instead of fixating in the subject-object divide that organizes Adorno’s discourse. If negative dialectics recognizes the impossibility of reconciliation, it still does so in a negative theological framework—Adorno’s devilish avatar in Mann’s Doktor Faustus is still pious, not diabolical enough, we might say—that Lyotard wants to shatter with the help of the contemporary avantgarde.

While any more precise references to the technical analyses in Philosophie der neuen Musik are absent in Adorno’s essay, it traces what I here have called the critical line in a precise fashion. The dissolution of the category of the work, the undoing of binding functions in musical language that renders the elements increasingly different to each other, the disintegration of time and its transformation to spatial structures that seem to exclude subjective mediation—for Adorno, all of these and many other analogous features evince the end of dialectics, even though they emerge dialectically out of the most advanced reflection on the musical material in the Second Viennese School. In 1949, Philosophie der neuen Musik can be taken to implicitly look back to a moment of subjective freedom that was lost (and necessarily so) in the ensuing flight into the enforced objectivity of serialism, to which Adorno would respond in a highly critical fashion in his writings in the 1950s with an attempt to reinterpret the history of modern music in a less linear fashion, in which Mahler reappears as an untimely possibility, together with Berg seen in a different perspective that connects him to the possibility of an “informal” music. For Lyotard, no such reactivating gestures are meaningful, rather it is the current breakthroughs in works of the avantgarde that point ahead, precisely in their undoing of the inherited categories of aesthetic theory that Adorno, no matter in how critical and mediated fashion, wants to preserve.

Cézanne and the work’s response

The claim that the work’s response to theory necessitates a reversal of the interpretative relation, even a challenge to the very desire for interpretation, can be found worked out In detail in Lyotard’s essay on Cézanne, “Freud selon Cézanne,” written the same year as Discours, figure.[5] Here Adorno is not yet present, instead Lyotard gives us his own twist of what Merleau-Ponty famously baptized “Cézanne’s doubt,” which was the point of departure for his idea of the exchange, on one level even a possible convergence, between painting and phenomenological research.

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire (1904-1906). Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

As the title indicates, Freud—or rather a traditional Freudian view of art that falls short of the claims elaborated at the same time in Discours, figure—is however the immediate target. Despite many attempts to show the complexity of the relation between art and psychoanalysis, and to dispel the idea of analysis as a diagnosis of the work as symptom, in Lyotard’s view, the relation has remained unilateral in the general sense that theory in the end is always applied to an object presumed to be a given, inert, and in need of being “read” to make sense. The resistance to this among artists and art historians is no doubt largely due to the relation’s asymmetry, which for Lyotard raises the question of a reversal, where the instituting and critical activity of art would be re-applied to the analysis, in turn transforming the latter into another work, unfolding on the same level as its former object. In this reversal Hamlet and Oedipus no longer appear as mere literary illustrations and examples, but function as operators, sieves, or epistemological grids that structure psychoanalytic theory, allowing tragedy to supply both the tools for, and a privileged representation of, the very logic of interpretation.

For Lyotard, it is no coincidence that painting provides a latent aesthetic analogy for the Freudian dream: both represent an absent object and open a scenic space where the representatives of things may become visible in their absence. As such, it is a hallucinatory scene, a mirage, and to grasp the object means to dissolve the image, to decipher the puzzle-picture by directing the signifying process back to language, placed at the beginning as well as at the end of the process. The artwork is taken to be mute and visible, situated at the locus of the imaginary fulfillment of desire. This it may bring about in two ways, either by allowing for an identification with the protagonists, or, as if an echo of Kant’s theory of autonomy, by its very position as a thing made for play, a toy or intermediary object that suspends our responsibility for our wishes; the artwork is a seduction at first sight, Freud says, which liberates energies previously bound up with repression. Here, Lyotard proposes, the aesthetic becomes a kind of “narcosis” that seals the work in the imaginary.

Leonardo d Vinci, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (ca. 1501-1518). Louvre, Paris.

The consequence of this is, first, a privileging of the represented objects or events, the sujet understood as an istoria located behind the Albertian window, and second, a quest for a form hidden beneath the represented object (the silhouette of the vulture inscribed negatively in the constellation of mother, Mary, and child, as in Freud’s reading of Leonardo in Eine Kindheitserinnerung des Leonardo da Vinci), both of which aim at the reduction of all non-representational features and the recreation of a lost discourse. As Lyotard suggests, this makes it impossible to approach works, and specifically those of the avant-garde, that take on the task of undoing the position of narcosis, precisely by transforming the canvas into an analogy to unconscious space itself, either by destroying the “dereality” (déréalité) of the work or by derealizing reality itself. These artistic revolutions were in fact contemporary with the invention of psychoanalysis, and they can be taken as fundamental subversions of precisely the representational space that is presumed in Freud’s understanding of artworks, while he in other respects was carrying out the same operations on the structures of consciousness. Both modern art and psychoanalysis, Lyotard states, are however ultimately surface effects of a subterranean revolution that shifts the very position of desire and the social logic of circulation and exchange in capitalism, casting down the mythical “Giver” (God, Nature) and releasing a system that henceforth only follows its own logic. To read Freud according to Cézanne thus means allowing them to infiltrate each other, drawing both towards a third dimension, which is that of the libidinal flows of Capital itself.

The problem that runs through all of Cézanne’s work is how to unify the object and its atmospheric envelope, Lyotard suggests, and what pushes him onward is the fundamental incapacity to achieve this, which is the source of the “doubt” identified by Merleau-Ponty. But as unity refuses to emerge, what the painter eventually discovers is that no such law of unity exists, that the painting will remain an impenetrable object without transparency. The dispersal of nature and consciousness is common to Freud and Cézanne, and neither the picture nor the psychic apparatus can ever achieve homeostasis. What remains are quanta of energy instead of signifiers, or a circulation of affects instead of a genetic layering of sense. At the core of this is a breakdown of the order of representation, and in this Lyotard agrees with Merleau-Ponty, but this does not mean that we can rediscover a true or first ordering of perception behind it; instead, the curvatures of Cézanne’s space, its inner imbalance, belong to desire, just as the natural object is always lost when placed in the space of desire.

To grasp this, no psycho-biographical correlations will be sufficient, since it is a question of a primordial loss that exceeds the formation of an ego whose life can be narrated. Rather, we should inverse the perspective and see the work itself as an analogy to the psychic apparatus, as a dispositif (whch here renders Freud’s Apparat) that binds and unbinds energy, thus allowing for an “economic aesthetic” akin to the Freudian economy of drives that would be liberated from the weight of representation. If Freud himself insisted on seeing the work as a hidden secret, it is because images for him were rerouted significations, screens that must be ripped apart to show their hidden content and force them to speak. Lyotard suggests that all of this is due to the primordial status accorded to Oedipus and castration, which the new libidinal thought must undo.

Such an aesthetic would also question Merleau-Ponty’s interpretation, where the doubt, as we have seen, relates to whether the painter’s descent into “les sensations colorantes” and the genesis of perception at all allows for a coherent painterly work, and whether “la réalisation” remains a possibility for the painter who has rejected the inherited tools of painting. In the end, Lyotard pits Cézanne against both the tendency of traditional psychoanalytical interpretation to see the image as a representation of an absent structure, and against phenomenology’s pious wish to find an anticipation of its own method in the painter’s work. What we must grasp, Lyotard suggests, is the extent to which the representational space into which Freud inscribes the work, and that Merleau-Ponty in his turn approaches from the point of view of its genesis in a perception brought back to the flesh, is already put in question by the artworks themselves. Cézanne and his followers invent a new object position, Lyotard claims, “the place of libidinal operations engendering an inexhaustible polymorphy” (DP 88) that allows for neither a harmony between self and world in terms of the flesh, nor a re-translation into a topography of the psyche.

Consequently, it is no longer a question of a discursive truth, in or as painting, as when Cézanne in one of his more optimistic letters wrote “I owe you the truth in painting, and I will tell it to you.”[6] For, as Lyotard writes:

In the last instance one does not paint in order to speak, but to shut up; and it is not true that the last paintings of Sainte Victoire speak or even signify; they are there, as a critical, libidinal body, absolutely mute, in truth impenetrable since they do not hide anything, that is to say that they do not have their organizing principle outside themselves (in a model to be imitated or in a system of rules to be followed); they are impenetrable since they have no depth, do not produce significations and have no obverse side (DP 88).

From plastic space to political space

The essay on Cézanne and Freud largely stays within the framework of a commentary on works that belong to the classical canon; the same year Lyotard also publishes an article, “Espace plastique et espace politique” (co-authored with Dominique Avron and Bruno Lemuel),[7] dealing with political posters that directly engage the political sphere. In this essay we find one of the most detailed explications of his approach in relation to singular works, and its arguments merit to be traced in some detail. Here too, the emphasis is less on the signified, more on the relation between social organization and the plastic surface or screen (écran), and on how plastic form relates to a “political unconscious,” with the aim to establish what is still called a “critique of ideology” (DMF 276/211), or a “deconstruction”—a term that recurs often in Lyotard’s writings from the period, but whose connection to its more famous counterpart in Derrida seems far from clear.

Just as in Discours, figure the analysis sets out from a distinction between textual and figural space, and then moves on to their mutual transgression through a particular kind of “work,” i.e., the dream-work as analyzed by Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams. While the poster is still an art object that mirrors other objects in a non-place, an empty space or “u-topia” (DMF 278/212), it draws social formations, fantasies, and energies into its inner formal organization in a way that in one aspect resembles the claims of Adorno about the parallel between social and formal analysis, in another aspect departs from it in de-emphasizing (though not entirely evacuating) the idea that what is internalized is a set of contradictions; as we will see, contradiction is rather like a local moment that, when thought through to its end, opens onto a more profound dispersal.

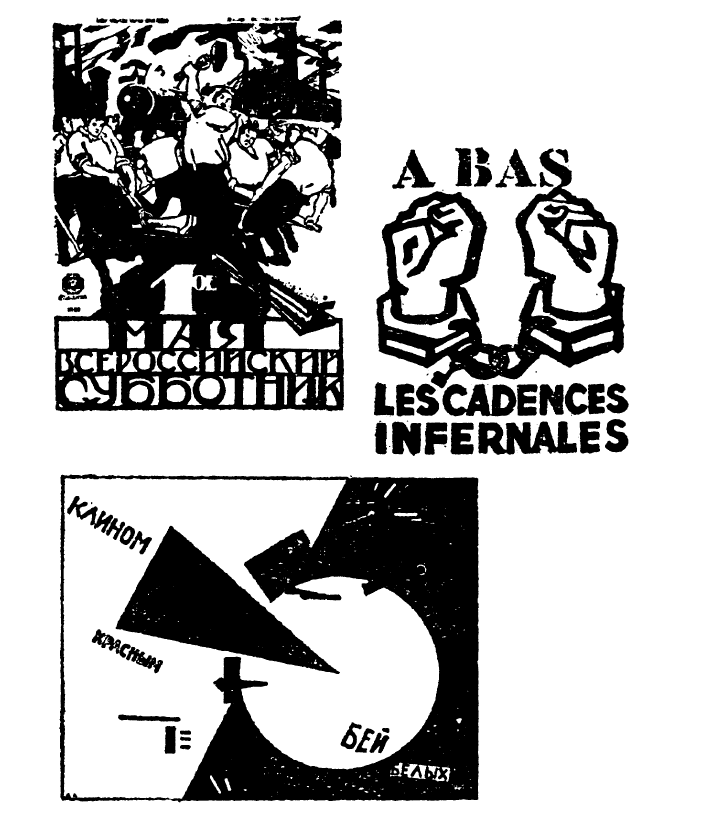

Three posters are proposed as case studies: one from the period from the aftermath of the Russian Revolution (1920), one from May 68, and one by El Lissitzky from 1919.

In the first Russian poster we find two pieces of text, “May 1” and “The Saturday Workers of all the Russias,” placed below a scene of work suspended on a festive holiday: a man striking an iron bar held on an anvil by a woman with tongs; another man wielding a pickaxe looking in the direction of locomotives and flags in the background. Everything converges on the anvil, and the vertical and oblique plane together establish the symmetry between text and image that makes up the unity of the poster.

The “1st” functions as a vertical dividing the picture, setting the stage as well as symbolizing the opening of a new era: socialism, the source point of history, the founding act, with the anvil as the base where a different world is forged, drawing on the demiurgic myth of Vulcan. But myth, Lyotard suggests, also “plunges ideology into an abyss,” and the connoted elements can be “invaded by meanings issuing from elsewhere which destabilize the unwieldy and ‘exact’ presence of ideology” (DMF 283/213).

The presence of “1st” is thus ambivalent: as a graphic and chromatic element it is dreamlike and floating, but through its legibility it fixes the image of the anvil and reduces its polysemia; the contradiction between free and ordered looking is contained and neutralized in the moment of reading. Similarly, the text is also a solid point of contact, it informs our view, addresses the image of the Russian workers of 1920. Image and text together constitute a “’reading’ game” (DMG 284/213), and it on this level, in the passage from image to text, that we can locate the properly utopian moment, reduced to an impalpable trace in the poster, with “1st” as a hinge, a relay between image and text through which the image posits it reality.

If the scene is fantastic, the text is like a stage apron, but precisely a text that precludes all other narratives, giving the figures only a dreamlike depth, and containing the anguish they otherwise might give rise to if released from their immediate function. The text produces an image into which I can resolutely project myself, that pulls the eye into its alluring space. In this sense, Lyotard can propose that the image is a “figure-desire, an action to be realized,” a “phantasmatic scene, needed to induce the viewer's desire, to make him take his desire for reality” (DMF 285/214). Reality survives only in “overexposed” traces (sledgehammer, tongs, anvil, railroad tracks), which are connoted, but also given a mythical attraction that draws me into the image: I am the one who swings the hammer, which creates a harmony between the principles of pleasure and of reality.

The second case takes us into the present. It is a poster put out by the metal industry, suffused with present-day ideology (whose content Lyotard does not specify), and the task becomes one of “deconstructing it, and then, perhaps, of destroying or unravelling it” (DMF 289/215; “unravel” for détourner here seems misleading; it is more a question of diverting, re-routing, of highlighting the movement of “drifting”)

The image can first be decomposed into three lines: the words A BAS (“down with”), the line of chained wrists, and the words LES CADENCES INFERNALES (“the hellish working rhythms”).

Lyotard notes that the first line is discontinuous with respect to word intervals, then also inside the letters, as if to indicate a work-like quality that we find on packing crates, barrels, etc., and that points to physical labor. Thus, the figural invades in the textural, while on another level the “A BAS” signals a cry of hostility and emphasis through the repetition of A.

On the second line we find the chained wrists, circumscribed by a continuous contour than transfers the tension from the exterior white space of the paper to the interior, while the former appears to spread out. Finally, LES CADENCES INFERNALES is discontinuous just like the first line, although the integrality of the letters is respected, and there is no longer any connotation of labor. LES and CADENCES are joined together, although the eye separates them, first because of the rules of the French language, but more importantly since the key on the handcuffs works like a caret in a proof.

The three elements are thus: A BAS, paradoxically placed on top, then the stylized hands, although with a certain depth that provides them with a hidden face, and finally LES CADENCES INFERNALES, which has an anchoring function, determines the floating chain of the signifieds and assures the viewer that the poster deals with the condition of industrial labor.

The position of the text below bars any escape route, as can be seen if we attempt to rearrange the elements. If we only would have the upper two and a smooth passage between them, the cry would seem to come from a mouth, or function like a balloon in a comic strip. If we would have just the wrists and the lower text, there would be exteriority, like the relation between image and caption. Faced with only the two texts, we would see the hiatus between them. If there was only the image, we would see its heavily written character, as if it were a figural element in a rebus. Consequently, it is the third element, the text below, that recuperates the space and transforms the image into a slogan, in which the desire to cast off the chains and free the hands remains blocked.

El Lissitzky, Клином красным бей белых!, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge!

The third case, the poster by El Lissitzky, provides a more radical option. Breaking with the horizontal-vertical system, it does not give us a surface in depth, but balances strictly by lines; instead of offering a window, it confronts us with a rectangle. The text inhabits the same space as the figure, the words becoming oriented along lines that lend force and movement to the reading: “wedge” (клином) and “red” (красным) are arranged according to two lines with their source in the upper left-hand corner, and they transfer energy to the red triangle.

The linguistic and figural space are thus mutually “deconstructed,” Lyotard proposes, which means that their reference to language as well as to art are displaced. Word and triangle interact in a field of attraction, so that the visual is not reduced, but restored in its depth of meaning as a dramatic process (whose political implications in the historical context are so obvious that Lyotard does not see the need to spell them out, even though they introduce precisely the kind of allegorical reading that he otherwise wants to dispel); so is “red´” related to the color of the triangle, but also to itself because of the lines circumscribing it and drawing it closer to the eye—they are the same thing, Lyotard writes, while “whites” (белых) is expelled from the white circle and pushed into a black area, set in gray color inside a white triangle, the gray indicating a passage from black to white, as opposed to “red” that contains the color within itself. The triangle destroys the circle, which is a closed figure foreign to the energy of the triangle, shattering the myth, so that the white circle eventually will be completely expelled. On the periphery of the white circle bits of red, black, and white rectangles and squares swirl around, like vibrant echoes, refracted colors rising to create a kinetic space.

On the level of the text, the position of the words disturbs the left-right reading order, and writing becomes spatial in a new sense: letters become figural material while yet remaining legible, which poses the problem of representation as a pseudo-deep space, but also the that of the body (vertical, balanced left-right). Reading, Lyotard suggests, can thus become a scanning with the entire body according to the pleasure principle alone, but also a scanning with the look or the ear, depending on our perspective.

In the struggle enacted on Lissitzky’s poster, Lyotard claims, the “red triangle is not the expression of the object ‘wedge,’ its abstraction, but the expression, unreifiable meaning, form and pure violence of sharpness,” a “’critique’ of ‘reading,’ of reference,” in a paradoxical text that “precludes a return to a space governed by perspective, a theater-form space” (DMF 299/219). Now, while this is true on the purely formal level of the poster, it unquestionably downplays the fact that the poster also refers to the signified “revolution” in a specific historical sense, without which its forms would remain abstractions and perform the same symbolic operation as the first Russian poster, even though using signifying elements of a different order. It is this suppression of representational content that allows Lyotard to suggest that the poster creates a free play, a space of contradictory energies that break away from the May 1st poster, where attitudes and sentiments are readable expressions of the body of humanism. The “pictorial” writing of images in the first poster, Lyotard suggests, is in the second superseded by a true creation of figures, or of the “figural,” where the quasi-depth of perspective gives way to what he here (in terms that immediately recall the vocabulary of Merleau-Ponty, which Lyotard would soon come to question) calls the “only real density—meaning” (la seul véritable épaisserur: celle du sens), so that “reading once again becomes legible: the seeing seen” (lire redevient visible; le voir vu) (DMF 299/220). In the Lissitzky poser, utopia for Lyotard implies the transgression of the interdiction separating the two spheres, which not just a “reassuring” revolution, or a linear search for truth and justice, but a desire for radical alterity also on the political level, whose precise meaning beyond its reassuring counterpart is however left suspended.

In the first poster social space is recovered through representation, a semi-realistic organization of space, with social stereotypes such as the steel industry (the Red Army). The plastic lines of force are submerged, subjected to the image as a window, through which the viewer must pass with his desire to enter the stage. This is an appeal to an already defined experience, the workers’ collective as subject, which rules out a critique of social space in its integrality, so that some regions of experience remain sheltered from overturning. Libidinally, the poster evokes the desire to repeat the formation of an organic unity (the work collective), and social space is used for ideological exploration.

The French May 68 poster has a similar function, although the evocation of desire here occurs through writing rather than through the image. The writing is doubly conventional, graphically as well as in term of the signified: it seeks recognition and to induce a familiar conduct. Libidinally, however, it evokes the death drive, and invites destruction rather than construction. The libidinal and political meanings are however contradicted by the plastic organization, in which the elements function like a compromise-formation: the manifest meaning is death, the latent meaning is belonging to a community.

In Lissitzky we find a plastic paradox, though no longer based in contradiction, which is the crucial move: a deconstruction of letters and words, but also a transformation of visual forms back to scriptural ones. Lyotard here sees a disappearance of the object following from the Suprematist critique of representation, in which forms and colors are entirely subordinated to their elementary power on the perceiving as well as on the erotic body. Here, desire cannot be lost in an object located in the imaginary, instead it meets the screen and is reflected on it in its sensible formal elements. The poster recalls desire to itself as flesh, rhythms, profiles, and it lacks objectification. Because of its lack of secure foundation, ii is also a space of unchecked anguish—a loss of object, without binding together, and the death drive prevails.

To beat the whites is not the only stake in a civil war, Lyotard suggests (which, as we have noted, is the obvious connotation of the image, here only referenced in passing), but rather to drive the wedge into all “white” zones of experience and ideology, to submit all that is instituted to a revolutionary reversal; everywhere the closed sphere of white “investment” must be broken up (investissement; it should be noted that unlike the English translation of Freud’s Besetzung, cathexis, the French translation forms a bridge between political and libidinal economy, whereas the German term has military connotations of “occupation”). On this level, Lyotard reads the three posters in terms of the economy of drives in Beyond the Pleasure Principle: in the first the destructive drive against the material prevails, but social unity is spared; in the second the death drive becomes manifest, but also an underlying desire for a community; in the third the death prevails, there is no recognition, no linking of communication to form a unity. The forms break the illusory fulfillment of desire, the lure by which Eros gives itself as reality.

The connivance of the principles of pleasure and reality that we see in the first two posters, Lyotard concludes, is the mainspring of ideology, and the critique of ideology carried out in the third example means quite simply to undo this link, which obviously raises the question how such a critical aesthetic of the death drive would relate to a revolutionary critique, to the revolution as a political project. Even if the avant-garde did not pretend to be a political avant-garde, as Lyotard notes, then the relation between plastic space and political space still seems highly tenuous.

Sound, body, voice

While music does not appear to play a major part in Lyotard’s writings from the period (as we noted, the essay on Adorno as devil largely bypasses the actual musical material), and his claims in this field have received only sparse critical attention.[8] Some of the early essays, especially those on John Cage and Luciano Berio, however, develop themes that are crucial for my attempt here to place Lyotard alongside Adorno. In the essay “Plusieurs silences” (1972), it is the idea of silence in Cage that allows Lyotard to propose his countermove to Adorno’s negative dialectic. The listening mode he finds delineated in Cage is an openness to a non-negative dispersal of the ego, multiplication in a form that no longer acknowledges loss and absence as a condition of possibility, instead capturing or folding together singularities deriving from a field that is pre-egological and non-subjective.

For noise or sound to become organized music, and for intensities or events to become an organism, Lyotard suggests that there must be inserted a kind of filtering mechanism that selects, or, in Freud’s vocabulary, a secondary elaboration that binds the primary process and its flows into recognizable forms. The system of tonality as well as other similar systems, for instance perspective in painting, are ways of providing this mechanism with a depth: the construction, as in the costruzione legittima of Renaissance painting or the Konstruktion in psychoanalysis, i.e. the establishing of a theatricality that is both temporal and spatial, binding all elements together.

It is on this level that Lyotard pits Cage against Schönberg/Adorno, but also against a certain tendency in Cage. Lyotard asks what it means to hear and/or to understand (entendre), and he suggests that there is in fact a “phenomenological schema implicitly at work in Adorno, but also in Cage: a unity of sense not yet made but always in the making, on the occasion of the world and together with it, a unity made up of sense. Or to put it differently: a sonorous world coming to itself in the unity of a body.” (DP 198)[9]

The phenomenological body is that which binds together, makes sense by filtering and excluding, and in this vein Lyotard can somewhat surprisingly suggest that it “requires the desensibilization of entire sonorous regions” (DP 199, my emphasis). To re-sensibilize these regions would then mean to render the subject open to a world without unity, not because it has lost some primordial oneness, but because it is made up of temporary resonances of events and singularities, where the inscriptions and the surface of inscription are not ontologically separate, but instead form two sides of the same libidinal band. This is a different, integral sense of sonority, examples of which Lyotard finds in Xenakis and Kagel, with particular reference to the latter’s Musik für Renaissance-Instrumente (1965-66), dedicated to Monteverdi, in which Kagel uses a set of pre-modern instruments, as depicted by Michael Praetorius in his 1619 Syntagma Musicum, to achieve an extraordinarily varied soundscape of colors and timbres (in fact reminiscent of Ligeti’s microtonal pieces from the same period, which were crucial for Adornos idea of an “informal music”) that also draws on contingent flaws in the instrument's engineering.

The world opened by Cage’s silence is thus not an absence of sound, but the emergence of plural and “unbound” sonorities where plenitudes and lacunae can no longer be opposed in terms of negativity or dialectics, since sound is liberated from its opposition to organized music.

When Cage says: there is no silence, he says: there is no Other who has the power over sound, there is no God or Signifier as a principle of unification and of composition. There is no more filter, regulated blank spaces, or exclusions: consequently, neither is there any longer a work, or a closure that determines the musical as a region. (PS 213)

This undoing of critical filtering in Cage’s aesthetic did not go unnoticed by Adorno, who clearly perceived the attack that it launched on the idea of autonomy. In an essay from the early 60s, where he was trying to sketch the possibility of an “informal music” that would escape the strictures of integral serialism and retrieve the sense of subjective temporality and freedom, he charged Cage with a “misplaced positivism” that “ascribes metaphysical powers to the note once it has been liberated from all supposed superstructural baggage,”[10] a naïve immediacy that takes upon itself to enact the dissolution of the ego carried out by late capitalism, or that “transforms psychological ego weakness into aesthetic strength.”[11] As we have seen, the reading proposed by Lyotard inserts itself precisely at this critical point, and attempts to discern an affirmative content in this stance; as Cage himself proposes, the issue was to gain access to sonorities and events that lay outside of the control of the ego, by way of an unfocused perception that displaces consciousness and intentionality—the goal is “self-alteration not self-expression,” as he says in one of his last texts.[12] The understanding of silence not as void and negation, but as a new form of dispersal and openness, can be taken as the crucial feature of such a “self-alteration.” This dismantling of the oppositional stance for Cage takes place on the level of perception, whereas for Lyotard it needs to descend below the level of perception and consciousness, and plunge into the libidinal flow, intensities, and pure differences; common to both is that the work does not so much seek to become a model of social relations, as to pass beyond them, or even forget them.[13] Only if we escape the model of consciousness and everything that is concomitant with it can we hear what is germinating inside these plural silences, and to turn “in the direction of no matter what eventuality.”[14]

The question is of course to what extent the dismantling of a certain kind of critical approach – “The Frankfurt School, a demythologized, Lutheran, and nihilist Marxism,” Lyotard exclaims (PS 213)—would be able to provide us with other resources, or if it in fact simply mimics the flows of capital itself. “There is no need to weep,” Lyotard continues, “we don’t want more order, a more tonal or unitary, rich or elegant, music. We want less order, more aleatory circulation and free erring: the abolition of the law of value.” (ibid.) But if is “capital itself that stages noises and silences” (PS 214), and if the law of value of late capitalism is not just as able to easily accommodate, but in fact consists in the production of such aleatory (in)differences, then we are placed at the very critical line that theory faces when it turns back on itself, in the sense that it is led to destroy those very distinctions, the diacritics of critique, upon which it is itself constructed. Lyotard is willing to accept this paradox head-on, and in fact the relation between these “several silences” proves to be critically undecidable: it fluctuates between a simple, straightforward affirmation and a different affirmation that somehow destroys that which it affirms; the task is a perpetual undoing also of undoing itself, to “destroy the work, but also the work of the work and of non-works” (DP 214)—all of which points to an indeterminacy that applies just as much to theory itself as to the musical (non)-work of Cage, as Lyotard understands it.

In the essay on Berio, “’A few words to sing,’: Sequenza III”[15] (with Dominique Avron), Lyotard discusses the composer’s work Sequenza III (1965) as a case of how music and language infiltrate and deform each other through the drives, in a way that parallels the analysis of writing and image in the three posters in “Espace plastique et espace politique.” But rather than the written, it is here the voice, the vehicle of sense par excellence, that is at stake. Berio bases the piece (composed specifically for Cathy Berberian) on a childhood memory of listening to the clown Grock, which for Lyotard implies the temporal paradox inherent in any attempt by a language of art to return to its lost origins—a paradox not to be avoided, but instead explored through timbre, intonation, and a variety of vocal gestures (the score gives no less then sixty-one directives for the vocal performance) that no longer fulfill a representational or rhetorical function, but present a rapid succession, even simultaneity, of affective states.

Picking up themes from the eighteenth-century quarrels between Italian and French opera, and their echoes in Rousseau’s writings on the origin of language as well as Diderot’s Le Neveu de Rameau,[16] Lyotard concludes that no reconciliation between primary and secondary processes can be achieved today. If Rousseau imagined that the two could be brought together in the “phantasm of a maternal language, language without articulation, language without father, without castration,” in Berio the “universe of maternal music is cut in two, the pieces can no longer be combined, we can no longer sing while speaking: the song is little more than speech pure and simple, and passion can no longer manifest itself than in the infrastructural disorder of words” (DMF 271).

Such attempted reconciliation is however what he perceives in a later works by Berio mentiond in passing Sequenza VII (1969) for oboe, where the recurring return to B appears to establish a tonal ground, but above all in Sinfonia (1968) for eight voices and orchestra. Here Lyotard sees the secondary process at work, traditional forms are cited, and “one fells that a return to tonal music occurs, so close to Mahler that it on the level can hardly be distinguished from him” (DMF 268).

Regardless of whether this is a justified comment on Berio (Sinfonia contains a wide variety of quotes, literary as well as musical, and there is an abundant literature on how they are integrated in the work in a highly conscious fashion),[17] the general drift of Lyotard’s complaint makes sense in the overall context of his claims. There is always a temptation inherent in the secondary process, a compulsion to retreat from what has been achieved to the relative safety of inherited languages; for Adorno, this would be signaled by the various forms of rappel à l’ordre from the Neo-classicism of the 1920s onwards, even though for him the attempt to re-connect, although critically, to the tradition cannot be rejected as such. For Lyotard around 1970, the unconditional move ahead, the imperative of Rimbaud’s—by then somehow already classical—imperative il faut ëtre absolument moderne seemed like the only option, whereas Adorno was in the process of retracting at least some of his claims about the modern art, with music as the paradigmatic case, as a one-way street, which is why the alternative between “modern” and “postmodern” seems particularly inapt to characterize the critical line nevertheless can be drawn between them.

[1] Lyotard, Dérive à partir de Marx et Freud (Paris: UGE, 1973), 20. Henceforth cited in the text as DMG with page number.

[2] Lyotard, La phénoménologie (Paris: PUF, 1954); Phenomenology, trans. Brian Beakley (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991). Henceforth cited in the text as Ph with page number (French/English).

[3] Lyotard, Discours, figure (Paris: Klincksieck, 1971), 9; Discourse, Figure, trans. Anthony Hudek (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). 3. Henceforth cited in the text as DF with page number (French/English).

[4] Adorno, Ontologie und Dialektik (1960/61), Nachgelassene Schriften, 4/7, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2002), 425.

[5] First published in Encyclopaedia Universalis (Paris: PUF, 1971); cited from the reprint in Des dispositifs pulsionels (Paris: Galilée, 1994 [1973]). Henceforth cited in the text as DP with page number.

[6] Paul Cézanne, letter to Émile Bernard, October 25, 1905, in Correspondence, ed. John Rewald (Paris: Grasset, 1937), 315.

[7] The text draws on seminars going back to 1968 and was first published in Revue d’Esthétique XXIII (1970), here cited from the reprint in DMF. Eng. trans. by Mark S. Roberts as “Plastic Space and Political Space”,” in boundary 2, Vol. 14, No. 1/2 (Autumn, 1985/Winter, 1986): 211-223. Page references given as: French/English.

[8] A notable exception is Suzanne Kogler, Adorno versus Lyotard: Moderne und postmoderne Ästhetik (Munich: Karl Alber, 2014). Kogler’s substantial and detailed study however came to my attention too late to be discussed here; I hope to return to it in a later context.

[9] It could be objected that Lyotard’s reading imports a psychoanalytic frame of reference that is wholly foreign to Cage’s aesthetic; the missing link, if one is needed, would in this case be Bergson, whose critique of negation is the direct source for Cage’s first formulations of the impossibility of a pure silence.

[10]Theodor W Adorno, “Vers une musique informelle” (1961), Quasi una fantasia, Gesammelte Schrifen, ed. Tiedemann (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1997), 16:509; trans. Rodney Livingstone, in Quasi una fantasia: Essays on Modern Music (London: Verso, 1992), 287.

[11] Adorno, “Vers une musique informelle,” 505; trans. 283. This is for Adorno an aesthetic strength that, precisely because of its lack of resistance to consumption, immediately passes over into surrender: “it degenerates at once into culture.” (535f; trans. 316)

[12] John Cage, Composition in Retrospect (Cambridge, Mass.: Exact Change, 1993), 15.

[13] For Cage’s view on cognition vs. perception, see “Experimental Music: Doctrine,” Silence (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1961), 15, and “Where Are We Going? What Are We Doing?” (ibid., 204f).

[14] Cage, “Composition as Process: II. Indeterminacy,” in Cage, Silence, 39.

[15] First published in Musique en jeu, no 2 (March 1971); cited from the reprint in DMF.

[16] Here too Lyotard crosses the path of Derrida; see the detailed interpretation of Rousseau’s writings on language and music in De la grammatologie (Paris: Minuit, 1967). For Derrida, the conclusion, if expressed in Lyotard’s terms, would to some extent be the opposite, and the very difference between primary and secondary process would form an integral part of the metaphysics of subjectivity in Rousseau.

[17] See, for instance, David Osmond-Smith, Playing on Words: A Guide to Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia (London: Ashgate, 1985).