CERFI, Desire, And The Genealogy Of Public Facilities

By Sven-Olov Wallenstein

I. Desire and socius.

Sometime in the beginning of the seventies, in the wake of May 68, a new way of conceiving the urban and the political emerges. “Modernism” – a term that will acquire as many senses as the sum total of its defenders and detractors – finds itself questioned in a wide variety of perspectives. The city suddenly becomes a text, a phenomenological space of experience, a historical palimpsest, a collage, a metabolic structure – and a form marked by complex power relations, a “machine,” overcoding materials and semiotic flows, that organizes desire in all of its forms. Here we will address such a debate, buried among historical documents, and up to now, inaccessible outside the Franco- phone sphere (for the most part), but whose repercussions extend into the present and the future, and where political, psychoanalytical, and philosophical themes intersect: the French research group CERFI.

CERFI formed, until the end of the seventies, a shifting network of independent researchers and political activists. The group staged an extra-academic encounter between psychoanalysis and the social and political movements of the period, and during its most active phase its president was Félix Guattari, whose experience as the director of the experimental psychiatric clinic La Borde was decisive for much of the work of the group (for a discussion of this, see Meike Schalk’s essay in this issue).

The earlier development, starting from the mid-sixties – which included the break with the French Communist Party – cannot be explored here, and its various ramifications and inner conflicts will remain in the background (for a study of the personal relations among the members, see Janet Morford, L’histoire du CERFI). The developmental line I will attempt to follow starts in the middle, with the research contract the group received from the Ministère de l’Equipement in 1971: how should the social demand for “public facilities” (equipements collectifs) be assessed, what does this demand signify, from whom does it emanate, and how can it be met?

Starting with a central distinction in Lacan between demand (demande – a verbalized expression determined by supply), and desire (désir – a phantasmatic projection), the question gradually acquired a new and, to the commisioners, presumably unexpected dimension. What is the desire that circulates in our institutions, how is it connected to the “axioms” of capitalism, to the city as metaphor, and to a concept such as territory? The seemingly limited, almost insignificant question of public facilities thus expands here and allows Marx’ analysis of capital to intersect with Nietzsche’s genealogical method, and with the productivist conception of desire that Deleuze and Guattari were developing at the same time: “We are fabricating a strange machine, made up of bits and pieces borrowed from the genealogist Foucault, stolen from the bicephalous savant Deleuze-Guattari and his construction site, or quite simply picked up from local artisans,” the editors state in the introduction to Recherches nr. 13, where the first results were presented.

In order to delineate the function of this “strange machine” we first have to scrutinize its constituent parts. However, we face the risk that this machine might finally prove to be a way of provisionally organizing a flow of associations and connections rather than a more stable theoretical unity with a clear function – but this provisional unity would also apply to the city, as it is stated a bit further on in the text: “The city is a computer which fabricates its own program, an information machine producing new information by constant mixtures, by controlling heterogeneous series, which, without this machine, would continue their homogenous unfolding separately.”

In L’Anti-Oedipe: Capitalisme et schizophrénie (1972) Deleuze and Guattari present the basic traits of the analysis of desire that we also find in CERFI. They suggest that we should cease to think desire as lack, castration, negativity, etc., but instead should think of it as production: desire is a machine (machine désirante). Deleuze and Guattari cite Lewis Mumford’s definition: “a combination of solid elements, each ha- ving its specialized function, operating under human control in order to transmit a movement and perform a task”.

It should be noted that this new ontology is often derived by commentators straightforwardly from Deleuze’s earlier work, for example his studies of Hume, Nietzsche, and Spinoza, which gives a partly biased picture. That which is decisive and new is that the Deleuzian ontology of difference is combined with a conceptual apparatus that Guattari had been developing since the early sixties, but whose specific, more developed features first appear only in Psychanalyse et transversalité (1972, the same year as L’Anti-Oedipe), and then in La révolution moléculaire (1977), and L’inconscient machinique (1979): the analysis of groups and institutions, the description of desire as constituting machines, assemblages, segments, lines, etc., are just as much derived from experimental clinical work and political experiences as from abstract philosophical considerations, and in the case of CERFI, the second aspect is no doubt predominant, not least because of Guattari’s role as president of the association during the decisive years.

II. The context: debates on urbanism

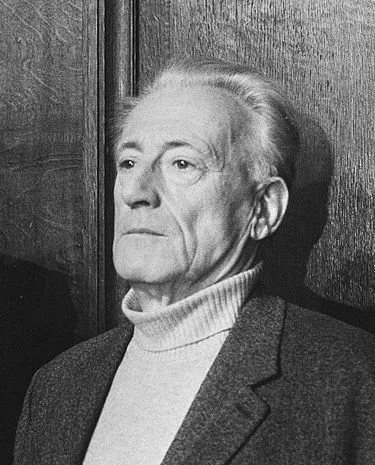

Henri Lefebvre.

CERFI’s work on the city and on the genealogy of public facilities also takes place, however, in the more specifically theoretical landscape of urban studies, whose main features we should now delineate, at least insofar as they concern the immediate French intellectual context. One of CERFI’s most important predecessors in urban sociology was Henri Lefebvre, who, immediately after the war, initiated a new form of spatial analysis, beginning with the first volume of Critique de la vie quotidienne (1947; the title recurs in two later volumes, in 1962 and 1981, and could serve as a guiding thread through his labyrinthine authorship). Lefebvre attempts to ground Marxist theory in an analysis of the structures of everyday life. These structures are, specifically, that which mediates between individuality and history, one of the consequences of which is that this intermediary level – as the place where alienation and reification occur and turn into experience – comes, to a large extent, to displace work as analytic category. This in its turn signifies a shift from the economic to the socio-cultural level, and develops into a critical reflection on the ideological role of “planning” (or l’amé-nagement du territoire, to cite the more broad French term) as the way in which modern state-governed capitalism annexes the life-world. Lefebvre’s critique of everyday life attempts to show how our experience is colonized by the State and by Capital, which function together as a leveling force, to which he opposes the constant potential for re- versal and transgression inherent in the everyday.

Lefebvre’s path would, at approximately the same time as CERFI’s dissidence within Marxism took shape, eventually culminate in a series of works focusing on the city and the urban question: Le droit à la ville (1968), La revolution urbaine (1970), La pensée marxiste et la ville (1972), and La production de l’espace (1974). The city, urban space, and modernity are the themes that connect the different elements of the analysis of the everyday and give it a marked spatial dimension. This analysis also signals a step away from the essentially systemic analysis of Marxism, which at the time – above all because of the role played by Althusser and structural theory – seemed to be moving in the opposite direction, away from concrete subjectivity toward the construction of strictly theoretical models within which individual experience is constituted as caught up in the imaginary.

The relation between Lefebvre and those involved in various aspects of CERFI – Foucault, Deleuze, and Guattari – given its particular intellectual milieu, is characterized by a strange mutual aggression and lack of comprehension. From another point of view, we could note that Lefebvre’s path from surrealism, through situationism (Guy Debord was Lefebvre’s student for a while at the Sociology Department at Nanterre, and he also was influenced in a lasting way by Constant’s ideas on architecture as “situation,” presented in the latter’s Pour une architecture de situation, 1953) and all the way up to the analysis of the “production of space” just as in Foucault, Deleuze, and Guattari, led him into a complex love- hate relationship with Marxism (Lefebvre was expelled from the Party in 1957), and they were all met by the same suspicion by official Party intellectuals. The absence of any productive dialogue between them surely has a lot to do with that “fetishism of small differences” which characterized the non-Party Left at the time, but also with essential theoretical differences.

Edward Soja has attempted to bring Foucault and Lefebvre together in his conception of “thirdspace,” but the question is whether this might erase the particularities in their respective positions. What separates them is their varying understandings of the historical dialectic, of the category of totality, and the status of subjectivity. For Foucault – if we allow for the reconstruction of an argument which as such cannot be found in his writings – Lefebvre is caught up in an illusory belief in the given, and is unable to see that this subjectivity and individuality is itself something produced, and thus is unable to function as a lever for resistance. Lefebvre would retort (and this point has been developed in an interesting way by Michel de Certeau in his work on “everyday life”) that Foucault does not grasp the contradictory and open qualities of everyday spatiality, but derives it immediately from a kind of panopticist diagrammatism. Foucault only uses the abstract concept of savoir, and never speaks of knowledge as concrete, connaissance, which means that he is unable to bridge the gap between the theoretical sphere and the world of practical action, and thus fails to see the potential of the everyday as well as the decisive role played by totality and centrality.

Without being able to reconstruct this interrupted – in a sense never begun – dialogue even in a sketchy manner, we may nevertheless note that it defines the parameters within which CERFI’s investigations of urban space and public facilities take place. Lefebvre however remains an indirect and mostly negative point of reference, whereas Foucault’s work is always central. From the early seventies and onwards he directs several parallel research projects at Collège de France dealing with the emergence of public institutions, and these projects intersect in many ways, even personal, with the activities of CERFI. During this period Foucault is attempting to think through, but also beyond (to a degree which is admittedly difficult to assess), the Marxist categories of social analysis: class, dialectical contradiction, determination in the final instance, the base-superstructure opposition, etc., all of these being questions that his earlier work from the sixties on madness, the clinic, and “epistemic orders” had left unanswered. His questions bear on the possibility of understanding the multiplicity of tactics and strategies that traverse the social field, whether all the micro-assemblages to which they give rise, and which function as the force-field providing stability and movement to the “order of discourse,” can be understood solely through the meta-narrative of the development of capital. It is well-known that, in this period, Foucault begins to understand power as coming from below, in terms of a “microphysics” as he will say a few years later: the big, “molar” macro-entities – State, Capital, Class – have to be dissolved into molecular functions. And it is the latter that, through a long series of convergences, can explain the emergence of the former, not the former that can explain the latter by orienting the movement of history toward a pre-given goal. There is no State, only processes of “becoming-state,” where the state may overtake and re- direct processes that do not stem from its own interiority, and that cannot be understood as expressions of its own logic.

Foucault’s genealogical method develops in a close, complicated dialogue with Nietzsche (as can be seen in the important essay from 1971, “Nietzsche, la généalogie, l’histoire”; see Brian Manning Delaney’s comments in this issue), but now it begins to be applied to questions relating to the materialization of power and knowledge in architectonic and urban forms. During the first years, Foucault’s research follows two main lines:

1. The first deals with the emergence of the figure of the doctor and of medical knowledge as a form of public authority (these investigations would later result in a much more encompassing theory of “bio- power” that opposes modern power and its function of supporting and producing life to the old sovereignty model and its privilege to “take life”), and whose material correlate is the modern hospital as a place where patients can be studied in isolation from one another. In 1977 the results of this project were published in the book Les machines à guérir (aux origines de l’hôpital moderne).

Foucault here looks back to his earlier studies, above all The History of Madness (1961) and Birth of the Clinic (1963), but with the difference that the “archaeology of the medical gaze” now becomes situated in an explicitly spatial and architectonic dimension, and not just in a theoretical and epistemological one. What emerges is a “curing machine” (machine à guérir), an expression coined by J-R Tenon in his Mémoires sur les hôpitaux de Paris (1778): a technology of power that allows for a new knowledge of the individual – and thus also for a new type of individuation – to develop, and where the architectural forms must correspond in a precise way to the new techniques of health care (whose function it is to separate, but also allow to circulate; survey, classify, etc.). This gives rise to a new building typology that no longer reflects academic concepts of form such as those of the Beaux-Arts tradition, but rather a multiplicity of new medical and other knowledges that at a given moment form a specific assemblage. This also produces a fundamental shift of our conception of the history of modern architecture, so that it can no longer be understood as a formal or tectonic-structural breakthrough, no matter where it may be located, but should instead be situated in a much larger terrain of knowledges and power. This historiographical polemic only surfaces incidentally, but it no doubt makes possible a genealogy of “the theories and history of architecture,” to use Manfredo Tafuri’s expression, that is different from the conventional one. These insights seem however to have exerted little influence on the kind of historical writing still focused on a description of forms and styles (which strangely enough also applies to Tafuri), which opens the possibility for a vast field of research: to write the genealogy of modern architecture as something different from both its “theories” and its “history.”

Nicolas Raguenet, The Fire of the Hotel-Dieu in 1772 (c. 1772)

The starting point for the debates that Foucault and his research team investigate is the big fire in Paris 1772, where the “General Hospital,” Hôtel-Dieu, is destroyed, which triggers a public discussion on the principles according to which such a public institution could be reconstructed. The previous institution, which mixed different categories of patients haphazardly, was subjected to severe criticism, although not only for its lack of efficiency, but also and more importantly on the basis of an emerging new concept of efficiency, productivity, and “curing capacity” that connects the hospital as a “public facility” (a term which would appear much later however) to the population understood as an object of health care politics. Blandine Barret Kriegel, in her study of “L’Hôpital comme equipement,” underlines how this affects the very idea of architecture, how the “distinction between the inside and the outside of the building is erased, and the rules applying to a building are extended to the whole urban facility (équipement urbain),” so that “the hospital system has to be reorganized at the level of the city.” The Academy of Science eventually rejects the reconstruction proposals of several famous architects (for instance Chalgrin and Ledoux) and replaces the idea of the building qua isolated object with a variable and functional facility that corresponds to the population as a whole, thus inaugurating the idea of “public hygiene.”

In another contribution, Bruno Fortier highlights how the functionalist imperative gives rise to a new type of urbanism that subjects the genesis of forms to a scientific methodology, and how the reconstruction of Hôtel-Dieu figured centrally in this process. Traditional authority figures were rejected, being replaced by new forms of knowledge (use of questionnaires to gather information, birth and mortality statistics, forms of demographic analysis). “Within the history of modernity,” Fortier writes, “the affair Hôtel-Dieu may be one of those moments when the architectural project is no longer understood only in relation to history, but as the function of a double imperative: both technological rationalization, and efficiency, in matters of discipline, economy, and power.”

2. The second line of research deals with the “politics of habitation” as it was formed during the first half the 19th century. The project eventually results in two main works, Généalogie des équipements de normalisation: Les équipements sanitaires (with an important preface by Foucault, published by CERFI in 1976), and Politiques de l’habitat, 1800–1850 (1977), where there is no written contribution by Foucault, even though his research directives seem to have influenced the different essays in a decisive way (the research team behind this publica- tion being to a large extent the same as in Les machines à guérir).

Politiques de l’habitat investigates how urban space was rationalized in the beginning of the 19th century, and how the “habitat” came to be systematically aligned with a new type of public space. In her introductory “Réflexions sur la notion d’habitat au VIIIe et XIXe siècle,” Anne Thalamy claims that “the concept habitat appears from early on to be rooted in a will to an urban order made up of defined and organized places with set functions: the house, a space for individual life – even though sometimes in a controlled form; the street, the privileged space for circulation but also for salubriousness – excluding congestion and uncleanliness; the stationary market, preferred over temporary stalls with their manifold sources of contact; injurious and unsanitary professions, activities, and functions are placed far away.”

What results is a tripartite structure: habitat, street, and city, a triad conceived on the basis of the idea that their mutual balance has been threatened and that order should be restored. In 1724 a royal decree on the city limits of Paris is announced, and a first systematic investigation of the city’s morphology takes place. The individual buildings have to be measured and described as part of a project of fixing the limits of the city and control the flux between inside and outside. Paris has to be mapped onto a grid, and made into the object of a surveillance, and a control, that require wholly new methods.

Eventually this system comes to focus on hygiene and the needs of the family. Materials, floor plans, behavioral patterns, etc., have to be permeated by economic rationalization, so as to optimize efficiency in the use of space. If medical science invests the health of the workers, then the habitat functions “as the instrument and mirror of morality,” Thalamy claims, just in the same way as the family forms “a kind of prism reflecting the habitation of the population as a whole.” Large and small scales, macro and micro levels, come to reflect each other in an increasingly detailed and regulated technique for analyzing urban space.

In his study of “Les demeures de la misère. Le cholèra-morbus et l’emergence de l’habitat,” Blandine Barret Kriegel shows how the idea of the habitat grows out of a need to control whole cycles of production and consumption in order to avert overcrowded living conditions and epidemics (the chief example is the big cholera epidemic of 1832): there is a need for a hygiene of the atmosphere, a control of air conditions, and for public health institutions able to monitor them, and police them with a force, a kind of “health police.” Medical topography focuses on infectious focal points where resources should be concentrated, but always understands them in the framework of the city’s health as a general problem. Danielle Rancière develops this theme in her essay “La loi du 13 juillet 1859 sur les logements insalubres,” where she investigates philanthropy and its connection with the state in the creation of a healthy working class. The problem becomes more complex when it comes to the open and the closed, air and light, etc. – too much transparency and circulation might lead to a “social contagion,” to idleness and moral depravity, and she formulates the problem in the following way: “The habitat of the worker has to be opened to the outside (air, light), and at the same time be closed off to the neighbors. Light has to be increased at the same time as visibility has to be reduced. A space is needed where currents of air can cross, but not the workers. The city has to be open and closed.” The problem could be termed the “squaring of the urban circle”: separate and unite at the same time, create a union that separates and individuates, that prevents illegitimate mixtures while also maximizing productive assemblages.

In the concluding essay, “Savoir de la ville et de la maison au début du 19ème siècle,” François Béguin once more emphasizes the mirroring of macro and micro levels, pointing to the status of Harvey’s analyses of the circulatory system as a fundamental analogy for the urban order. This renders the single architectonic object even more relative, and inscribes it even further into an overarching urban and social logic (a fundamental intuition in CERFI’s research too, as we will see later on). Béguin proposes that “it is no longer the subtle play of imitation and variation [in relation to the tradition, S-O W] that regulates the construction of architectonic forms, but a constant adjustment of the architectural norms to other norms whose scope and content wholly escape the power of the architect.”

In this way architecture becomes open to the admittance of other disciplines (which we also saw occurring in the case of the hospital) – hoards of external specialists are summoned forth, something that the architectural discipline for a long time refuses to acknowledge, which leads to a false self-consciousness, and Bégun notes that it is only at the beginning of the 20th century and in “functionalism” that an explicit attempt is made to overcome this division. He develops the theme on the basis of a fascinating quote from Adolphe Place (taken from a review in Encyclopédie d’Architecture, May 1853): “A house is an instrument, a machine, as it were, that not only serves to protect man, but as much as possible has to comply with his needs, support his activities, and multiply the results of his work. In this respect, industrial constructions, manufactures, and factories of all sorts, are indeed worthy of imitation.” It is as if Le Corbusier’s conception of the house qua “living machine” here begins to be generalized and spreads outward concentrically, starting from the hospital paradigm and then through other facilities into the habitat, even though the aesthetic and architectural vocabulary required to express it – a vocubulary which might also conceal its modernity, of course, given that this formal language also tends to reactivate a classical discourse in beauty – would take another 70 years to develop.

This functionalization also pushes the analysis beyond the confines of the house, from the habitat to the street and then to the city. The task, Béguin proposes, is to “derigidify, demineralize, deconstruct the house.” Gas, water, air, light: all of them are external variables that penetrate the house and make it part of a larger logistic network; conversely we might say that every interior, every domestic universe, is a result of a process of domestication. The different “apparatuses” (where “apparatus” needs to be understood broadly) connect it to the outside, and we have to historicize these technologies so that they can be understood as parts of “one big project to restructure the whole of the urban territory.” We move from domestic apparatuses to “mega-urban” apparatuses, and Béguin takes water and water conduit systems as the example of a long and stratified technological development, and shows how the idea of enclosure, of habitus, is dependent on an increasingly fundamental interconnectivity.

III. Capital and the genealogy of public facilities

In CERFI’s journal Recherches (nr. 13, which brings together material from 1971-73), preliminary results of the team’s research are published, and the different contributions are brought under a rubric that in a symptomatic way combines Nietzsche and Marx: “Genealogy of Capital.” This is by no means a systematic theoretical exposé, but rather a series of sketchy essays, transcribed discussions (translated below), personal reflections on the internal erotic, financial and hierarchical relations in the group (entrusted of course to the female participants – in a sexist fashion typical of the period), and other texts of rather fragmentary character. (The theoretical contributions are unlike those that reflect on the group dynamic in the further sense that they are published anonymously, and while it would be possible to reconstruct individual authorship, I choose to treat the text as a collective product; for a list of the participants, see the bibliography below). But despite, or perhaps because of, this stylistic heterogeneity, the journal is, as Daniel Défert claims in his essay, “Foucault, Space, and the Architects”, “one of the most interesting log books from the ideological crossings of those times,” where one “as if in a laboratory experiment watches the fissuring of Marxist analysis and the emergence of what would soon be named the ‘postmodern attitude.’” Regardless of whether the term “postmodern” is adequate to the task of capturing this displacement, we can see the dismantling of a whole gamut of traditional urban and sociologi- calling for other categories, while the new analytical tools proffered remain highly insecure and tentative.

As Françoise Choay notes in her influential anthology from the mid- sixties, Urbanisme: Utopies et réalités, the architecture culture of the period was split between two main positions: a functionalism rooted in CIAM’s Athen Charter, and a culturalist attitude focusing on preservation of the cultural heritage. Recherches opens by citing Choay’s remarks, but then proceeds to an analysis of these two solutions as mirror images of each other: both of them understand the modern city as fundamentally sick, and thus also see it as their task to propose a solution. Both of them also see public facilities in terms of consumption, where that which is consumed is either function/utility, or symbolic values.

A hidden precondition for there being an alternative in the first place is, however, that one assumes the existence of a subject of consumption who would precede the facilities, and that the consumption would occur within the register of representation. Now, CERFI does not want to invalidate any of these positions as such; instead they want to uncover an “epistemological socle” that makes the very alternative possible in the first place. The point is to understand the city as “production,” and the public facilities as the means of production. This is why the analysis does not bear on ideology, but on a process that takes place on the unconscious level. To use the terminology from Anti-Oedipus: it would be a schizo- analysis of the city (for more on this topic, see Helena Mattsson’s contribution to this issue). The city becomes a machine that produces itself –“a signifying machine that does not signify, but gathers, connects, and redistributes all types of chains: productive, institutional, scientific, etc.” The city itself becomes a kind of public mega-facility, which, in its turn, is inscribed in a larger territorial organization, which again is part of an even larger system knowing no limits. The city becomes a fixating and stabilizing machine that on a certain level overcodes and connects flows that originate on a lower level and continue on a higher. This however soon leads to the question of whether the category “city” can be an adequate analytical category at all, which is the real topic of the seemingly abstruse arguments about whether the city and public facilities deal in “production” or “anti-production” in the first discussion, translated below.

The following section, “The city-metaphor” (written in 1972) draws this conclusion, which was implicit already in the former, namely that the city is nothing but a metaphor, an empty container or a surface for the projection of various concepts whose proper function, however, has to be understood within a larger system. “We used the word ‘city’ for what is really relations of social production, forces of production, Capital or even the State.” The city, the authors remark, through a subtle displacement, easily turns into a personification or a hypostatized historical subject endowed with a life of its own (as in, for instance, Lewis Mumford or Fernand Braudel). They propose, thus, that “the discourse on urbanity should itself become the object of an archeology, its reference should be deconstructed.”

In Marx too they find indications of such hypostatizing, for instance in The German Ideology, or The Communist Manifesto. Both of them, notwithstanding their historicizing of all categories, tend to understand the system country-city in a non-historical fashion, which allows, tacitly, the form of the presentation to be organized according to an irreversible path leading from country to city, something which Marx without further ado characterizes as the liberation from “rural idiocy.” What could equally well have been understood as oppositions between different cities within a given territory – for instance on the basis of conflicting “interests” of different producers – always comes to be overcoded by the abstract opposition countryside-city.

It is highly significant that this is also the context in which Marx places the genesis of ideology. Resulting from the separation between material and intellectual labor, it has as its “most essential precondition” the separation between countryside and city – “the very passage from barbarianism to civilization,” as The German Ideology has it. The theme runs through Marx’s whole work, and it does not disappear in the later works. Thus CERFI argues against both Althusser (and Manuel Castells, whose Althusserian 1971 work La question urbaine is another important point of reference), whose thesis on an “epistemological break” in Marx, where he allegedly frees himself from the dialectical-humanist metaphysics of his early writings, results to a positive evaluation of this development, and against the dialectical humanist Lefebvre who remains sternly critical of such a passage from “subject” to “system.” For Althusser, Marx’s abandonment of concrete subjectivity in favor of an abstract and systematic totality means that individual experience can no longer be anything but an imaginary reflection, and we can now proceed to understand the individual as constituted via an “interpolation” within ideology; for Lefebvre this is a false view of the potential of everyday life, and ideology would rather consist in the dream of a “pure theory” (and the corresponding dream of a pure subject capable of thinking it). But this stubborn opposition, the authors in Recherches claim, in fact hides “the underlying points of fracture,” and allows them to be overlaid with a whole set of oppositions: nature-culture, barbarism-civilization, knowledge-ignorance, impurity-purity, artificiality-authenticity, etc, which all remain caught within the same duaist model. Neither subject (experience) nor system (pure theory, structure) are sufficient concepts, instead we have to find a series of concepts that cut transversally through the opposition between the dialectic of experience and structuralist system analysis, that open the opposition up to that which passes through both subject and system.

What we need to see, CERFI claims, is that there is no such thing as the city, an entity that would stand in opposition to an equally abstract countryside, but rather there is only a network of cities, which in its turn expands into a concept of territory – and it is this which might be the proper object of analysis. Through this, two tasks crystallize: on the one hand, there is a need for a theory of territoriality that accounts for both its openness (that it has no de jure limit) and its closure (the State overcodes a given territory, inscribes its signs onto it in order to make it into its own body); on the other hand an analysis that comes back to public facilities, although no longer in terms of physical architectonic objects, but as complex assemblages of power and desire, i.e., as objects of what we, following Nietzsche, could call a genealogy.

We may leave the development of the concept of territory aside here, even though many of the theses advanced in connection with territory are highly interesting (and they could be connected to Foucault’s as yet unpublished seminars from the second half of the seventies on security, territory, and the genesis of the modern state apparatus). In any event, at the end of the third section, in the passage leading to the question of public facilities, the territorial organization of early industrial capitalism is summarized in three points that we should note: 1. The city fixes the population around an industrial function (the example being mining cities in the north of France, which organize the habitation of the workers so that everything comes to revolve around the mine); 2. The city as a whole can therefore be seen as “a public facility for territorial fixation,” and a paradigm case of this would be, the authors note, Bentham’s Panopticon model, where “all the elements in the territory of the facility are monitored in such a way that they are all aware of it in every moment” (and here we may recognize a theme which Foucault would develop two years later in Discipline and Punish); 3. The family becomes an invested object, and habitation comes to form a part of the system of public facilities. In this sense, the family is by no means a remainder from earlier forms of society, but a new object produced at the dawn of industrial capitalism.

In the introduction we noted that the analysis of public facilities is based on a Lacanian distinction between needs (or explicitly stated demands) and desire. The radical thesis proposed here is that the need for facilities is an illusion, or rather a retroactive rationalization, a thesis to a great deal influenced by Foucault’s investigations of how the discursive object “madness” – an object we can could talk about, analyze, fear, seek to control secretly or approach as a subversive force – is produced by the “Grand Internment,” i.e. a physical institution that gives rise to manifold effects on all level of knowledge, instead of emerging as an answer to an already existing need. It is true that the population should not be understood as a passive and malleable mass; however its activity should not be understood in terms of given needs, but rather through the desires it sets in motion, and we have already the wide sense in which desire is here to be understood.

Thus we should not understand public institutions as responses to a need, or as motivated by a function that would remain permanent throughout history: “one can never explain a public facility by its use in a system of needs: what has to be brought to light is the forceful gesture (coup de force) that gives rise to it as an instrument of subjection, dominance, and repression.” This does not mean to deny function and use, or to see them as mere ideologies, but, the authors claim, to understand them as “mechanisms of inscription that produce collective facilities as instrument of coding, internment, limitation, and exclusion of free social energy.”

Without being able to follow in detail how this is developed in analyses of the hospital, the school, and many other institutions, we can still summarize the theory of public facilities in five central theses (that the authors propose just before the second discussion, translated below, where the argumentative line once more is broken and leads in a new direction):

1. The person or the subject, as that upon which the new facilities converge, is not an anthropological given, but an “effect of the movement by the forces of the unconscious, which at the same time are social forces of production, are registered and distributed over the surface of social institutions, where they determine a field of representation, which thus also comes to apply to the person or the subject.”

2. The family is just as little originary as the person; the modern marital bond displaces the old large family, and comes to play a decisive new role in the modern system of production.

3. Public facilities inscribe, codify, and give rise to a “territorial fixation” of the flows that have been released by the destruction of the pre-capitalist order.

4. They produce normalization on the basis of a whole gamut of distinctions: the healthy and the pathological, worker and unemployed, reasonable and insane, etc.

5. Social needs cannot explain the facilities, instead the State/Capital produces, in one and the same movement, the facilities, the family, and all the corresponding “needs.” The “genealogical turn,” the authors claim, “has as its aim to dissolve the objectivity of needs and the whole system that articulates it.”

In this sense, the genealogy of public facilities does not provide us with any normative theory of the development of institutions, it does not tell us what good State, Society, or Man, ought to look like. The gaze of the genealogist creates distance and difference, but in this also a certain type of release. The debate in Recherches remained inconclusive by all standards, but there are many zigzag lines that extend from it to our problems today, to the conflict between urban “renewers” and “preservers,” whose “epistemological socle” surely remains to be uncovered.

Sources

Publications by CERFI and Félix Guattari

Recherches no. 13: Généalogie du capital. 1: Les équipements du pouvoir

Recherches No. 14: Généalogie du capital. 2. L'idéal historique

Recherches No 25: Le petit travailleur indéfatigable

Recherches No. 46: L'accumulation du pouvoir, ou le désir d’Etat. Synthèse des recherches du CERFI de 1970 à 1981

Félix Guattari, Psychanalyse et transversalité (Paris: Maspéro, 1972)

La révolution moléculaire (Paris: Éd. Recherches, 1977)

L’inconscient machinique: Eléments de schizo-analyse (Paris: Éd. Recherches, 1979)

Anne Querrien, Devenir fonctionnaire et/ou le travail d’Etat. Lectures hypothétiques sur l’histoire du corps des Ponts et Chaussées (Paris: Ed. CERFI, 1977)

Projects directed by Michel Foucault

Les machines à guérir (aux origines de l’hôpital moderne) (Brussels: Mardaga, 1977)

Politiques de l’habitat, 1800–1850 (Paris: Corda, 1977).

Généalogie des équipements de normalisation: Les équipements sanitaires (Paris: Éd. CERFI, 1976)

Texts on CERFI

Daniel Defert, “Foucault, Space, and the Architects”, documenta x: Poetics/Politics (Stuttgart: Cantz, 1998)

Janet Morford, Histoire du CERFI: La trajectoire d’un collectif de recherche sociale. Mémoire de D. E. A, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (Paris, 1985)

An expanded version of the section on CERFI has been published as ”Genealogy of Capital and the City: CERFI, Deleuze and Guattari,” in Helene Frichot, Catharina Gabrielsson, and Jonathan Metzger (eds.), Deleuze and the City (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016).