The Landscape of Aesthetics

Sven-Olov Wallenstein

Review of: Jacques Rancière, Le temps du paysage: Aux origines de la révolution esthétique (La Fabrique Editions, 2020); Lytle Shaw, New Grounds for Dutch Landscape (OEI Investigations X, 2021)

Landscape and the system of the arts

“The art of the painter, as the second kind of pictorial art, which presents sensible illusion in artful combination with ideas, I would divide into that of the beautiful depiction of nature and that of the beautiful arrangement of its products. The first would be painting proper, the second the art of pleasure gardens.”[1] Kant’s proposal in the Critique of Judgment, placed in a section where he delineates his take on the system of the fine arts, sets the stage for Jacques Rancière’s recent exploration of landscapes and gardens, not only as new elements in the system, but also as crucial for the emergence of aesthetics.[2] Kant’s comments insert themselves in a tradition that was already underway throughout the eighteenth century; Rancière points to Thomas Whately’s Observations on Modern Gardening (1770) and Christian Cay Hirschfeld’s Theorie der Gartenkunst (1779), and, on a different note, to Julie’s “secret garden” in Rousseau’s La nouvelle Héloïse, but, as he remarks, the tradition of using the garden as an image of perfection can be extended as far back as one wants. The crucial shift that occurs from the seventeenth to the eighteenth century, and which warrants Rancière’s use of the term “aesthetic revolution,” is however that landscape not only was included among the fine arts, but also, and more fundamentally, “imposed itself as an object of thought” (9). For this to happen, the discourse of design skill and perfection, as well as that of the medical use of the garden, had to give way to a theory of pleasure, a new “distribution (partage) of the sensible,”[3] to use a term employed earlier by Rancière—a redistribution not only of objects, but of subjects as well, which in turn amounted to a fundamental change in the structure of experience as whole.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, La Nouvelle Héloïse, illustration from the 1761 edition.

This pleasure arises from the imitation of nature: “Nature—that is, all of reality plus all that we can readily conceive to be possible—is the prototype or model for the arts” (“La Nature, c’est-à-dire tout ce qui est, ou que nous concevons aisément comme possible, voilà le prototype ou le modèle des arts”), as Batteaux had written in Les Beaux-Arts réduits à un même principe (1746).[4] This nature is however always there in the form of a beautiful second nature, la belle nature, resulting from the assembling of the dispersed traces of beauty of a first nature into a coherent whole that speaks to human passions. But how can a fine art imitate nature by using its own products? For Kant, the figurative arts were divided into those whose ideas were embodied in sensible forms, as in the plastic arts, and the art based in appearance, i.e., painting, but contrary to what would seem obvious, he places gardening as a subdivision within painting. Unlike architecture, it has no external purpose, and it does not treat its objects as materials for construction, but as appearances destined to produce pleasure in the play of imagination, of earth and water, air, and light. Rancière suggests that “play” should here not be taken as a straightforward dematerialization, but instead in the sense that the frontier between the natural elements and the use of light and shadow on the surface of painting has become “porous,” in a “movement that begins in the play of natural elements and is continued in the play of forms, and shakes up the faculties of the mind in order to make them play freely among themselves” (22). Echoing Rousseau, this also provides a moral lesson that directs the mind toward ideas, as Kant underlines both in the sphere of beauty and in that of the sublime. Rather than representing nature, art picks up, continues, and intensifies a process without fixed limits: “Nature is no longer a model that should become recognizable in the different forms of its imitation, but rather a movement that traverses and animates the universe of the arts, coming from elsewhere and pushing beyond it.” (26)

But in this, as Rancière suggests—which is the second key claim of the book—it also signals a new sense of the political. If the “time of the landscape” coincides with “the birth of aesthetics, not in the sense of a particular discipline, but as a regime of perception and of the thought of art,” it also “contemporary with the French revolution, not in the sense of a series of more or less violent institutional upheavals, but of a revolution in the very idea of that which assembles a human community.” (10)

Nature as artist

In this shift, it is nature itself that appears as “dramatic artist” (30) and presents us with “scenes” (a term picked up from Whateley), which provides Rancière with an early and crucial link in the series of “scenes from the aesthetic regime of art,” as was the subtitle of his earlier book Aisthesis.[5] This new perception blurs the division between art and nature, it destabilizes the positions of “the model and the copy, of the work and the artist, of the artist and the non-artist” (121), and in this it prepares the advent of Art as such in Romanticism, beyond the system of the individual arts. Henceforth, nature no longer signifies a set of laws linking cause and effect, but a free spontaneity without a pre-ordained plan, which escapes the grasp of the inherited academic discourse of harmony and symmetry that previously underpinned the idea of the geometric garden and its mastery over nature.

Rancière traces, with many details, how the appreciation of landscape mutated in the course of the eighteenth century: the idea of “vastness” in Addison, Hogarth’s “intricacy” and “serpentine line,” continued more systematically and with political implications by Burke, who opposes the “smooth” curve of harmonious societies to the rational and authoritarian order of the French garden, and then staged in a manner just as grandiose as oppressive in the parks created by Lancelot “Capability” Brown (whose nickname derives from the “capability for improvement” that he saw in the gardens he set out to remodel), who ruthlessly displaced entire villages in order to realize his visions.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Harewood House, from the South (1798). The surrounding park designed by Capability Brown.

Towards the end of the century some of these concepts eventually ended up in opposite camps, and the followers of Brown were pitted against proponents of the picturesque like Uvedal Price and Richard Payne Knight. Significantly, for the latter, the art of nature essentially consists in that it itself brings the intricacies of irregular forms together into a unity, in which the accident displaces the line, while the aristocratic park of Brown rejects any spontaneous assembling emerging from below. The political implications of this are obvious, as Rancière notes later in the book (98f), not least in the use of “enclosures” that via parliamentary decrees would displace the older “commons” that was essential for the life of the rural poor).[6]

As Rancière remarks, in the discourse of the system of the arts, the relation between painting and landscape harbors a paradox on another level as well. If the theory of the picturesque can elevate art above nature, it is because painting, as a “science of the gaze” (56), forms the basis for the new perception of landscape. This perception requires a thoroughgoing aesthetic education that teaches us to find perfection even in the seemingly imperfect, just as we can prefer a vivid sketch to a slick painting, and it makes it possible to constitute a whole new genre of objects as candidates for appreciation, beyond the inherited hierarchy of genres of painting. If painting must draw on the spontaneity of nature’s self-forming, this nature must somehow already be perceived through the lens of painting.

In the idea of intricacy there is also an idea of a limit, in the sense that incompletion must somehow be constitutive, so that the visible always comes up against the invisible, which will later become one of the basic tenets in Kant’s theory of the sublime. In Rancière’s reading, however, the subsequent tradition’s emphasis on the duality between the beautiful and the sublime overlooks two intermediary concepts, the picturesque and the grand, which were instrumental in making the the landscape into a source of aesthetic education. In Burke these two fill out the gap between beauty and sublimity; for Kant, however, the two once more come apart, indicating that the sublime cannot be attached to any material form, but belongs to the mind alone, and the landscape must be dissociated from the supersensible ideas that it awakens.[7]

The landscape of politics

These ideas all have their resonance in politics, and the event of the French revolution can be taken as the moment when they coalesce into a contradictory unity. For Burke, the revolution signals the end of the sinuous line and smoothness, and the imposition of a rigid Cartesian order on the winding paths of a landscape that accumulates traces of history without erasing them. For others, for instance a writer like Wordsworth, this Cartesian landscape instead indicates a general equality, open for all, whereas the aristocratic tastes of Burke imply an illicit transferal of historically determined features to nature. As Rancière writes: “A landscape reflects a social and political order,” just as a “social and political order can be described as a landscape” (95)—but the passage between the two is by no means simple and harmonious, as is indicated by the projections of the “English” and the “French” onto each other.

Thus, as we have noted, he construction of “vastness” in Brown and his followers in fact required considerable violence and the displacement of large segments of the rural population, and it spawned popular protests. It in this context that the proposals of Knight and Price can occupy a middle position on the political level as well, where “intricacy” is joined with “connectivity,” so as to avoid both a revolutionary fervor and an arrogant creation of vastness only aimed at the delectation of the landed rich. Just as in the rustic scenes of Gainsborough, the image is that of a gathering of people, animals, and natural “incidents,” brought together in the space of the “commons.” As Rancière notes, in a text like Price’s Letter to H. Repton we can see facets of Burke’s political theory transformed into precepts for painterly composition, in which the “gradations of the social order become gradations of light on the canvas,” dissimulating social inequality in the “atmosphere of a beautiful evening” (108). The naturalization of politics is already guided, we might say, by a politicization of nature that makes into an image of the harmonious totality that politics itself is unable to achieve.

Thomas Gainsborough, Hilly landscape with peasant family at a Cottage Door, Children playing and Woodcutter returning ca 1787.

In Kant, at last as read by Rancière, this unity comes apart, and the irregularity of nature, when linked to the sublime, will cease to prefigure a human community—which for Kant, as one must note, is still the case with beauty, and particularly so natural beauty, which Rancière quickly passes over to move on to Hegel. Hegel has little interest in landscaping and the art of gardening, which he mentions briefly towards the end of section on architecture, added to the final part on “Secular Architecture in the Middle Ages,”[8] where his analysis curiously stops, long before he would have reached the period dealt with by Rancière. This lack of interest is part of a general disinterest in natural beauty as such: what is important for Hegel is beauty born in spirit and returning into spirit, i.e., works that express human subjectivity in its historical unfolding, not judgments that in fact can bear on any kind of objects, as in Kant. In fact, natural objects are frequently more relevant for Kant when it comes to the role of aesthetics in the architectonic of reason, and specifically so in the case of the sublime, which he explicitly severs from judgments on artworks, since they inevitably bear on the measure of the human body, whereas Schelling, Hegel, and the subsequent generation of thinkers will return the sublime to the sphere of art. For Hegel, if nature can be appreciated as beautiful, it is not because it is an artist that creates scenes, but only to the extent that it is mediated through our subjectivity. It is significant, Rancière notes, that when Hegel cites Dutch painting, his examples are not the landscapes of Ruisdael or Hobbema but works that show human industry and practice.[9]

For Rancière, the reading of this transformation as the advent of the autonomy of art—with its ensuing claim in Hegel that art is a “a thing of the past”—is too simple,[10] and the intrusion of “non-art” into the system of the arts, which was the effect of the introduction of the landscape, will go on: art will search for new model, which Hegel could no foresee, especially through new constellations of technology that will endow nature with an open-ended series of implications.

Mud musings

If Rancière focuses on the emergence of landscape as an aesthetic category, and on its role in the complex process of the gradual unfolding and subsequent blurring of the concept of art, then Lytle Shaw takes a somewhat different route, though not without intersections with Rancière’s. In New Grounds for Dutch Landscape he proposes a reading of three painters, Jan van Goyen, Jacob van Ruisdael, and Meindert Hobbema (two of which also appear en passant in Rancière).[11] Shaw’s project is not to account for the shifts in the representation of landscape that would usher in the Enlightenment as analyzed by Rancière; instead he steps back to the preceding century and explores painting’s own way of retracing the process of the reclamation and formation of landscape, and the recurring obstacles that nature puts to human control.

Rather than images of a social order prefigured in the pleasurable intricacies of landscapes and gardens, inflected by as well as inflecting painterly perception, the Dutch masters highlighted by Shaw provide us with a world of “drainage problems, flooding, abrasion and erosion of the ground plane,” with “low-level dramas of recalcitrant matter”[12] that always threaten the reclaiming of land from the sea with imminent failure. Thus, instead of celebrating the successes of engineering, painters turned their works into mud puddles to show the frailty, even futility, of human industry, as in van Goyen’s Dunescape (1629), where Shaw sees “the reversal of differentiation that is the mundane, everyday narrative of erosion, wood decay, sand-dune drift, road migration, and mud-pool movement” (23).

Jan van Goyen, Dune Landscape with Cottage and Figures, 1629.

Via negativa this comes across in Ruskin’s attacks: in Dutch painting, he complains, humans appear as mere figurines in a landscape that thwarts them, sinks them into mud, so that nature and shapeless forces take over, displacing the sense of beauty, morality, and religion.[13] But rather than fending off these allegations, Shaw turns them into a strength: this type of painting is not only akin to draining and reclaiming swamps and bogs, but draws these processes into its very facture. Thus, instead of inserting the works in larger social and political history that would explain them, Shaw’s materialism attempts to “dig down into a domain of social significance that is there in the painting, drawing meaning directly out of the muck depicted in seventeenth-century landscape paintings, and from their mucky means of depiction.” (13)

These landscapes of entropy and sedimentation—the occasional references to Robert Smithson are obviously crucial, and Rauschenberg’s Mud Muse is surely never far away—also engage a different sense of time than the one suggested by Rancière. The time of landscape for Shaw rather means a depth that stands in opposition to history and humanist landscape painting: it is a resistant microtemporality that he opposes to the monumental history of great events, of which the French revolution, as it appears in Rancière’s narrative, would the most obvious example. But beyond this, he also pushes the famous analysis of Svetlana Alpers, who pits the narrative logic of Renaissance art against the synchronic, gridded “mapping” techniques of Dutch paining, in a different direction.[14] Shaw’s stubborn materialism is a materialism of the paintings themselves rather than a claim to deduce them from overarching social structures or from ideal-type representational models like optical distance vs. haptic proximity; it is the intrusion of matter itself in the sphere of experience (and, to engage in a perhaps slightly ignoble play on words, where would Bataille’s base materialism find a more suitable setting than in the Pays-bas...).

If the emergence of landscape as an object of thought for Rancière implied a porosity between elements of nature and elements of painting, so that in the end nature itself could be taken as the primordial artist (although in a way that was always already informed by painting, in a supplementary movement linking art and nature in a continually deferred mirror exchange), then for Shaw too, nature in a certain sense becomes an artist in Dutch painting; it is a nature akin to Spinoza’s monism, where God and Nature merge into a process of forming and deforming—although a God no longer expressing himself in the distinct and definable modes and attributes of rationalism, but through formless substances, slime, and mud, a monstrous materiality into which the hope of an elevation to philosophy’s “adequate ideas” of the world appears to have been submerged beyond salvation.

Puddles

In this descent into matter, Jan van Goyen is the paradigmatic painter of mud, “the basic condition out of which all life (and all representation) emerges” (70). Humans seem, in varying degrees, to fuse with or emerge out of the ground plane and the muddy intermingling of water and land, as if their erect posture was an achievement of sorts. The restricted and subdued color treatment envelops the figures in an undifferentiated atmosphere, binding them to the earth and the soil. In Dune-Landscape with Figures, the “largest part of the painting’s ‘ground’ is a dark, swirling mudslide,” and apart from the figures “the entire ground of the painting is a non-ground” (71f).

Jan van Goyen, Dune-Landscape with Figures, 1632.

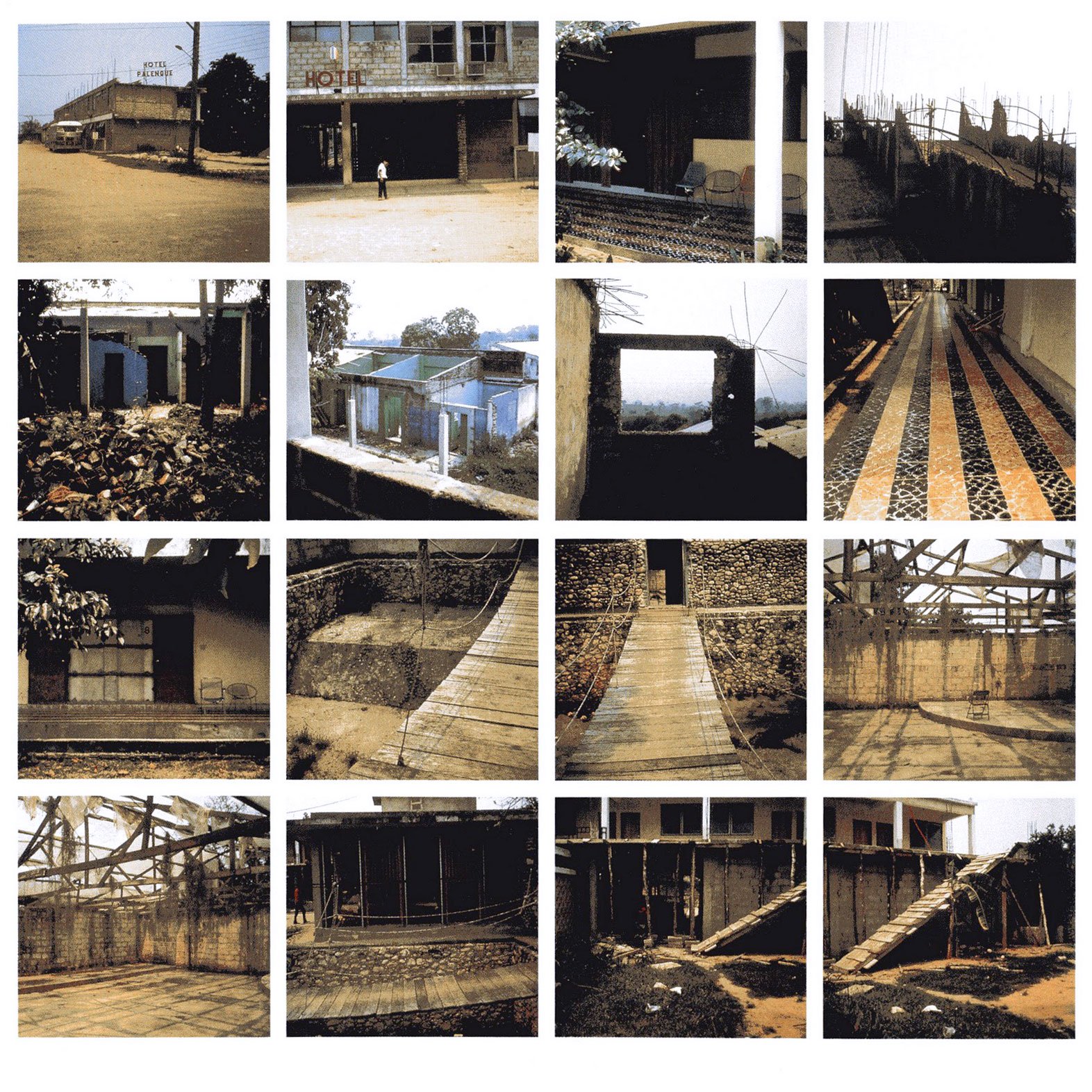

Picking up Hegel’s comments in the Lectures on Aesthetics, “that what nature affords directly to other nations, [the Dutch] had to acquire by hard struggles and bitter industry,” and that the task of “getting a footing in the prose of life” led them to “grasp this most transitory and fugitive material, and to give it permanence for our contemplation in the fullness of its life,”[15] Shaw asks whether this footing for van Goyen, the son of a shoemaker, was not a more complex operation that we must not stride past too quickly. The ground refuses to be fixed, and remains a “pockmarked, swirling, entropic earth surface” (76) that always threatens to derail human planning, cause the beams of cottage houses to protrude and their thatching to decay—somehow in advance prefiguring Robert Smithson’s take on the ever-unfinished Hotel Palenque as a process of de-architecturalization, as Shaw suggests in a footnote (58 note 47).

Robert Smithson, Hotel Palenque (1969-1972). During his stay at the hotel Smithson made photographs of the building, recording its cycle of simultaneous decay and renovation. The work consists of 31 slides and an audio recording of a lecture by the artist at the University of Utah in 1972.

Van Goyen’s project, Shaw suggests (once more echoing Smithson),[16] is about suspending differentiation and returning elements to a pre-sorted state, the “universall Quagmire” of which Owen Felltham spoke in his records from travels in Holland (cit. on p. 77), and which other earlier writers, such as Karel van Manders in his Schilder-Boeck (1609) had attempted to give a pagan but still venerable descent by tracing it back to the primordial chaos in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. This is also what we, perhaps more surprisingly, find in another contemporary thinker, Descartes, whose unfinished treatise Le monde portrays such a world in the making, even though he would later, Shaw suggests, after the verdict passed on Galileo, undertake a “cleanup operation” (84) with the imposition of the geometric grid; the Dutch painters however preferred to stay with the lump rather than move on to the grid. In fact, as Shaw proposes, this can be taken as a moment of the genealogy of modernism, in the trajectory Impressionism to abstraction: the “over all-quality” of the paintings, merging foreground and background, surface and depth, constitute an (in)formal breakthrough of sorts, indicating that the claims about the grid as the decisive precursor of abstraction must be seen in conjunction with the opposite claim about the importance of a pre-geometric, fluid, and aquatic element.

Torrents

In Jacob van Ruisdael, it is less the inertia and resistance of mud than an energetic movement that is at stake: floods, waterfalls, torrents that sweep the landscape, a “particular kind of blurring that occurs when water speeds up and atomizes as it descends over rocks” (135). The breaking of the dike was always a threatening possibility, unleashing forces not of gradual decay, but of rapid inundation and destruction; Ruisdael’s water, Shaw suggests, has not yet been domesticated to become a resource of irrigation and fertility, but emerges as a “pre-national liquid” (140) against which the ingenuity of engineering must always struggle.

Jacob van Ruisdael, Landscape with Waterfall and Logs Blocked by Rocks, ca 1670.

Another element that comes to the fore in Ruisdael is sand, as the underlying ground of the cultivated landscape, and it can always reappear as the surface is rubbed down by those walking on it, in a kind of “alchemical transmutation: sand can become landscape for the Dutch in the way that paint can become landscape painting” (144). Thus, in Road Through an Oak Forest, the zone of erosion forms the center of the picture: “a worn-away plane of vegetation, mostly vertical surface, that runs between a small hillock and a road that curves elegantly around it.” (146)

Jacob van Ruisdael, Road through an Oak Forest, 1646-47.

Ruisdael’s roads and paths, Shaw proposes, involve a sense of walking. Picking up Alois Riegl’s analyses of Dutch portraiture,[17] which highlights the new compositional strategies that avoid the focalization on a single person in Italian history painting, and suspend external action in favor of a gaze directed toward an inner mental sphere, Shaw discerns in Ruisdael’s wandering and straying figures a dilation of time, an “ongoingness” (153) that evades the discrete event (and even more so the major events that are there by implication in in the “time of the landscape” as interpreted by Rancière). But as Shaw also notes, partly following Julie Berger Hochstrasser,[18] this stretched-out time stands in opposition to the increasingly regulated and regimented time of transportation systems, commerce, and trade, which forms the other side of Dutch seventeenth century social life. Landscape painting is in this sense as much shaped by what it renders visible as by what it makes invisible, even though Shaw stresses the actual painterly presence of the vast array of commodities that circulated through the country. Rather than reading the landscapes as resulting from a repression of grim realities of slave trade and capital, Shaw however perceives in them a “progressive posthumanism” that must be distinguished from “regressive inhumanity,” in “decentering man from the landscape, and opening a new relation to time” (161) that pits the loss of human sovereignty in the face of nature against orders of social domination.[19]

This loss opens towards disorder, most visibly in the fascination with ruins and dilapidated structures, but, as Shaw points out, unlike the craze for crumbling Roman architectures that would sweep across Europe a century later, shrouding the present in a mythical past, Ruisdael’s drawings of ruins were ruins of the immediate present.

Swamps

If van Goyen leads us down into mud as the originary element, and Ruisdael immerses us in flows and torrents that produce a differentiation of the elements, then Meindert Hobbema’s world is one of swamps, lakes, and pools, the thresholds between land and water.

Meindert Hobbema, Woodland Road, 1670.

Once more, in contrast to the reading of landscape as reflecting and expressing human actions, from Diderot to Michel Fried,[20] Shaw notes how Hobbema’s strollers have to stake out paths that take “present and possible water in this terrain” into account, a “shifting set of possible trajectories through space, disruptions and occupiable locations”—unlike the humanist temporality of the landscape, this is a eventless duration that “creates a painting, too, that can wander” (205). Rather than actions, we are drawn into the picture by elements like trees and drifting clouds that form an “ongoing surround” (206), a world of which each painting can be taken as an aspect linked to all others.

The intermingling of land and water produces the particularly amphibious quality, zones of still murky water and swamps. To move in a landscape such as the one depicted in Farmland with a Pond and Trees (1665), Shaw notes, is to “survey the changing character of such swamps and millponds” (210), just as the artist draws on his imagination not to transcend the narrow world he has built up for himself, but instead to entrench himself more deeply in the minute details of those non-features that for someone like Ruskin are unworthy of attention; Hobbema does “not know when to stop,” Ruskin exclaims, and he is “evidently incapable of even thinking of a tree, much more of drawing it, except leaf by leaf.”[21]

Meindert Hobbema, Farmland with a Pond and Trees, c. 1663-1664.

Hobbema provides us with a thing-based space in which human figures find their place, often resting or casually strolling, as if confirming Hegel’s claim about Dutch art as an art of leisure and the eternal Sunday. But, as Shaw proposes, this non-instrumental stance towards objects does not entail leisure, but rather a decentering of the focalization around human endeavor: among seventeenth-century Dutch landscape paintings, his are ultimately “the least about man’s special position in the order of things, his sovereignty over the surround” (227). Hobbema’s swamps slow down perception, halt motion, like the huge logs in the foreground of many paintings. His “non-instrumental now,” Shaw proposes, empties the landscape of those characters and events that makes up the backbone of the humanist landscape; as if with a gesture that in advance rebelled against Capability Brown’s projects, he “evicted landscapes sovereign landlords and invented a non-instrumental duration” (239).

Aesthetics of landscape, landscape of aesthetics

Rancière’s and Shaw’s respective books provide two substantially different perspectives, and not simply because the pose different questions, engage chronologically and geographically distinct sources, and have unequal ambitions—Rancière’s study is more of an extended essay, whereas Shaw’s is a three-hundred-page work with an almost infinite plethora of notes and references. But it would be just as misleading to account for the difference as one between a philosophical and an art historical approach; more fundamentally, it is a question of two different conceptions of time and history as such. For Rancière, despite his earlier misgivings about the historicizing of logical categories, the “time of the landscape” denotes a historical moment, basically the Enlightenment, when the emergence of landscape as an “object of thought” signaled a redistribution of the sensible with profound effects on art, philosophy, and politics, and as such, it appears to play a crucial part in the emergence of what he in earlier books called the “aesthetic regime” of art. For Shaw, time is the form of the landscape itself, an entropic time that to some extent remains outside of, or at least precedes, historical events and human actions, which is why if offers a profound resistance to the humanist categories through which a long tradition of critics from Diderot to Ruskin to Fried have approached it. The Dutch quagmire would in this sense constitute something like the flipside of the aesthetics of landscape; it would be the landscape underlying the aesthetic, a “new ground” that is just as much a non-ground that gives way under our feet as we attempt to survey and inscribe it in our projects.

The “porosity” between art and nature that Rancière finds in the eighteenth-century perception of landscape appears like a step on the way towards the advent of Art as such that we find in romanticism, above all Schelling, which is where the formula that nature has become an artist acquires its full meaning, and where the boundary between art and non-art begins to break down through in an expanding movement. In Shaw’s version, this threshold is as it were crossed in the other direction; the significance of the works under scrutiny is not just that natural elements enter into their very facture, but that they, in their “progressive posthumanism,” would return culture to nature and somehow give us access to a hon-human time that would deliver is from the weight of oppressive social structures.

It may seem ridiculously superfluous to object that such claims cannot be but metaphorical: van Goyen’s paintings may be about mud, but are not made of mud, just as little as an aesthetic that proclaims nature to be an artist cannot mean that artworks would come about through natural processes (even Spiral Jetty was, after all, made by Robert Smithson, and not by the Great Salt Lake). The “muck depicted” and the “mucky means of depiction” that Shaw bring together in his many painstaking descriptions and analyses yet belong to different worlds, the first to nature and the second to the domain of artistic technique, and “to draw meaning directly of the muck depicted” cannot but in the end remain an illusion. Similarly, the opposition between the humanist theory of landscape and the Dutch master’s diminishing of the role of the human figure remains an intra-aesthetic opposition, and cannot, at least as I see it, validate any claims made by posthumanist philosophies of the Anthropocene, or speculative realisms or materialisms that today want to erase the nature-culture divide. I am not sure how far Shaw would be willing to go in that direction, even though it now and then seems to appear between the lines.

In the case of Rancière, landscape had its time as a scene in which the unfolding of Art began, with its subsequent forays into domains of non-art, leading up to the “indistinction between that which is art and that which is not” (125). If Shaw’s proposal might be that we need to bring aesthetics back to its ground in the materiality of sites and spaces, Rancière’s might be that the inclusion of this new materiality was only a step towards the generalization of the aesthetic, beyond which it loses its defining outside. In this sense the two books address each other, as if seeing the same elusive object from opposite sides. Which side we take—if any—is perhaps more dependent on philosophical sensibility, even taste, than on any specific argument.

[1] Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft, Werke, ed. Wilhelm Weischedel (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1974), 261 (§ 51); Critique of the Power of Judgment, trans. Paul Guyer & Eric Matthews (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2000), 2000.

[2] Already at the outset the reader might note an ambivalence between garden and landscape: while the garden obviously is a human product with enclosures fencing it off from the surroundings, the landscape is not man-made and does not present itself as having any fixed boundaries. That this distinction becomes relative in painterly representations does not invalidate it on the first level, but in Rancière’s text the two sometimes appear as interchangeable. It is, for instance, indeed possible to extend the metaphor “garden” as far back as one wants, as Rancière suggests, but surely not the metaphor “landscape.”

[3] Le partage du sensible: Esthétique et politique (Paris: La Fabrique, 2000).

[4] Charles Batteux, The Fine Arts Reduced to a Single Principle, trans. James O. Young (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 6.

[5] Aisthesis: Scènes du régime esthétique de l’art (Paris: Galilée, 2011).

[6] As Laurent Folliot notes in a review of Rancière’s book, these themes have been dealt with in Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (London: Chatto & Windus, 1973), and John Barrell, The Idea of Landscape and the Sense of Place, 1730-1840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University.Press, 1972), and The Dark Side of the Landscape: The Rural Poor in English Painting 1730-1840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), which constitute crucial references in the discussion of the politics of landscape. For Williams and Barrell, the poetic and pictorial treatment of landscape and rural life are ideological through and through, and they serve to obscure the economic realities that made the artistic perception possible. See Folliot, “De l’ordre de la nature à l’ordre social,” in La vie des idées, October 12 (2020): https://laviedesidees.fr/Jacques-Ranciere-Le-temps-du-paysage.html. For a critique that similarly emphasizes the material dimension, see also Paul Guillibert’s review, “La nature est révolutionnaire,” Contretemps, January 10 (2020). https://www.contretemps.eu/nature-revolutionnaire-ranciere/

[7] It should be noted that that Kant never uses the term “landscape” (Landschaft) in the third Critique, but instead, as in the sections on the sublime, speaks of a nature that fundamentally threatens our existence. “Bold, overhanging, as it were threatening cliffs, thunder clouds towering up into the heavens, bringing with them flashes of lightning and crashes of thunder, volcanoes with their all-destroying violence, hurricanes with the devastation they leave behind, the boundless ocean set into a rage, a lofty waterfall on a mighty river, etc., make our capacity to resist into an insignificant trifle in comparison with their power.” (185, § 28; trans. 144).

[8] See Hegel, Vorlesungen die Ästhetik II, Werke, ed. Karl Markus Michel & Eva Moldenhauer (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1986), 14:349f; Hegel’s Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art, trans. T. M. Knox (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), II:699f.

[9] But it must be added, also a moment of leisure that have been picked up by many commentators: Dutch art, Hegel famously writes, is the “Sunday of life”; Ästhetik III, Werke 15:230; Aesthetics, II:887.

[10] Hegel’s claim that “[i] n all these respects art is and remains, with respect to its highest determination, for us a thing of the past” (“In allen diesen Beziehungen ist und bleibt die Kunst nach der Seite ihrer höchsten Bestimmung für uns ein Vergangenes”) (Ästhetik I, Werke 13:25; Aesthetics I:11), has been interpreted differently, but I think most commentators today agree that it in no way implies a simple cessation of art. Freed from its “highest vocation” to express the absolute, it becomes the object of aesthetic pleasure, historical erudition, and many other attitudes among producers and recipients alike, and in this sense it remains entirely open to the inclusion of former “non-art” forms and contents in Rancière’s sense. For a discussion of Hegel’s proposal in the Berlin lectures, and how they pick up and modify themes from his earlier works, notably the Phenomenology, see my “Hegel’s Art-Religion in the Phenomenology of Spirit and Beyond”, in Ivam Boldyrev & Sebastian Stein (eds.), Interpreting Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit: Expositions and Critique of Contemporary Readings (London: Routledge, 2021).

[11] See Le temps du paysage, 117. Two earlier books by Shaw have been published by OEi Editör in Swedish translation, Fältarbeten: Från plats till site i nordamerikansk efterkrigspoesi och -konst, trans. Anders Lundberg & Jonas (J) Magnusson (2016), and teori med små bokstäver och den platsspecifika vändningen, trans. Jonas (J) Magnusson (2021).

[12] Shaw, New Grounds for Dutch Landscape, 14. Henceforth cited in the text with page number.

[13] [W]e lose, not only all faith in religion, but all remembrance of it. Absolutely now at last we find ourselves without sight of God in all the world.” John Ruskin, Modern Painters (New York: John Wiley, 1879), 5:253, cited in Shaw, 78

[14] Se Svetlana Alpers, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century (London: John Murray, 1983I.

[15] Hegel, Vorlesungen über die Äshetik II, Werke 14:225-227/I:597-599.

[16] Recalling a visit to the slate quarries in Bangor-Pen Angyl, Pennsylvania, Smithson notes how “[a]ll boundaries and distinctions lost their meaning in this ocean of slate and collapsed all notions of gestalt unity. The present fell forward and backward into a tumult of ‘de-differentiation,’ to us Anton Ehrenzweig’s word for entropy.” Smithson, “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects,” The Writings of Robert Smithson, ed. Nancy Holt (New York: New York University Press, 1979), 89, For Ehrenzweig’s notion of de-differentiation, see his The Hidden Order of Art: A Study in the Psychology of Artistic Imagination (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1967), and, for Smithson’s take on the term, Gary Shapiro, Earthwards: Robert Smithson and Art after Babel (Berkley: University of California Press, 1997), 88-93.

[17] Alois Riegl, The group Portraiture of Holland, trans. Evelyn M. Kain & David Britt (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1999).

[18] Julie Berger Hochstrasser, “Inroads to Seventeenth-Century Landscape Painting,” Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art, vol. 48 (1997).

[19] On this point I cannot entirely subscribe to Matthew Rana’s claim that Shaw “largely circumvents questions surrounding the painters’ respective relationships to Dutch colonial enterprise.” While it is true that this dimension does not a central role in the book, it does surface at many crucial points, and one cannot say that he ignores it. The problem as I see it is instead theoretical and has to do with how we should articulate the two levels, the loss of human sovereignty and social domination, and in what sense the first can provide a precise critique of the second. See Mathew Rama, “Mudbound”: https://kunstkritikk.com/mudbound/

[20] See Fried, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), and Shaw’s discussion, 202f, 246f (note 20 and 21).

[21] Ruskin, Modern Painters 1:398, cited in Shaw, 216.